Brexit deal done: the key dates in the UK exit from the EU

Long-awaited trade deal struck days before deadline

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A trade deal has been struck between the UK and the EU, days before the 31 December deadline.

The treaty will come into effect from 1 January 2021, taking over from the existing transition period arrangement. The deal will need to be ratified by parliament, with MPs potentially being called back early from their Christmas break to vote on 30 December.

At the beginning of 2020, more than three years after voting to leave the, the UK formally departed as a member state. But the country will now cut ties with a deal, over 1,500 days since David Cameron resigned on the steps of Downing Street.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Since then, Brexit has claimed the premiership of Theresa May and will define the leadership of Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Given how long the saga has rolled on, you would be forgiven for having forgotten how we got here. Here are all of the key dates.

23 June 2016 - UK votes to Leave

Despite contradictory polling results in the run-up to the EU referendum, most commentators expected Brits to opt to stay in the European Union. Even as the count was under way, UKIP’s Nigel Farage said it looked like “Remain will edge it”.

However, the Leave campaign won by 51.9% to 48.1%, a gap of 1.3 million votes. David Cameron announced his resignation as prime minister the following day.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

13 July 2016 - Theresa May becomes PM

Then home secretary Theresa May won the Conservative Party leadership contest by default, after all her challengers fell away.

“No new PM in the modern era will have entered Downing Street with an in-tray as full and fateful as hers,” said The Times. “She will have to reconcile her desire to ‘make sure our economy works for everyone’, which depends on growth, with Brexit, which is likely to hurt it.”

May’s arrival at No. 10 brought a “culture change” at the top levels of government, “sweeping away the Cameron clique” of Old Etonian pals and replacing them with “grammar-school grafters”, said Polly Toynbee in The Guardian.

17 January 2017 - Brexit means Brexit

In her first substantial speech on Brexit, May said that remaining in the single market would mean being bound by EU laws, which “to all intents and purposes, would mean not leaving the EU at all”.

The speech revealed her desire for what has become known as a “hard Brexit”, setting out the Government’s 12-point “Plan for Britain” and her negotiating red lines, ruling out membership of the EU’s customs union in the process.

29 March 2017 - trigger warning

On this day, May triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, formally kick-starting a two-year countdown to the UK exiting the bloc.

The Guardian’s front page featured an image showing a jigsaw puzzle of the EU, with the UK pieces missing and replaced with the headline, “Today Britain steps into the unknown”. Not to be outdone, The Sun physically projected the words “Dover and out” across the legendary White Cliffs of Dover.

8 June 2017 - snap general election

After calling a snap election in a bid to increase her authority on Brexit in the Commons, May lost her parliamentary majority and was forced to make a deal with the DUP to stay in power.

Following the general election, “May’s reputation crashed, arguably faster than any other in modern British political times”, said the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg.

“It humbled her, weakened her, leaving May a ‘wounded antelope’, in the words of one of her senior colleagues.”

8 December 2017 - birth of the backstop

Following a series of late-night negotiations in Brussels, the UK and the EU agreed a deal on the UK’s so-called divorce bill, covering both EU and UK citizens’ rights and the so-called Northern Irish “backstop”.

But the New Statesman’s Stephen Bush predicted that there would be trouble ahead over the Ireland border issue, writing: “Many of the stated objectives of Conservative Brexiteers won’t be fulfilled thanks to the obligations the United Kingdom has agreed to secure sufficient progress.

“Yes, the United Kingdom is out of the single market and customs union in law - but agreeing to the necessary alignment in order to preserve the open border means that our laws will still be controlled de facto if not de jure in Brussels.”

6 July 2018 - Chequers, mate

After the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill became law at the end of June, May took her cabinet to her country retreat Chequers in order to sign off a collective position for the rest of the Brexit negotiations with the EU.

But trouble was afoot, with Brexit Secretary David Davis resigning over May’s new plan. Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson followed Davis out the door, before describing the deal as a “suicide vest” for the British Constitution.

25 November 2018 - backstop’s back

Following some enforced changes to May’s Chequers Plan at the behest of the EU, a 599-page draft Withdrawal Agreement was published that contains a fleshed-out backstop which angered both the DUP and the Tory’s Brexiteers.

Under the deal agreed between May and Brussels, the backstop would have kept the whole of the UK very closely aligned to EU customs rules, with some regulatory differences between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

15 January and 12 March 2019 - once more with meaning

Having pulled the vote before Christmas over fears that she would lose, May attempted to get her deal ratified by Parliament on 15 January.

But with Brexiteers worried about the UK remaining in the customs union through the backstop, and the DUP concerned about potential disparity between Northern Ireland the UK, the PM suffered the heaviest defeat in modern parliamentary history, losing 432 votes to 202.

Further legal assurances from the EU about the temporary nature of the backstop were not enough to quell Brexiteer rebellion, and May lost a second meaningful vote on her deal by 149 votes two months later.

12 April - the end of the beginning?

In April, the UK’s deadline for leaving the UK was pushed back to 31 October - with or without a deal - in the wake of May’s failure to push a deal through the Commons.

In the wake of the announcement, speculation over whether the EU would be willing to give the UK more time come October was rife, sparking major disagreements.

Germany’s foreign minister Heiko Maas told the Financial Times: “They will have to decide what they want by October. You cannot drag out Brexit for a decade.”

The continued impasse in Parliament led to a renewed belief that a general election would have to be called before October to break the deadlock.

Polling from Politico found that the Brexit culture war dividing the UK continues to polarise voters.

“Leave voters in the East Midlands and Northwest are moving toward the Tories and away from Labour, while Remain voters in the Southeast are shifting in the opposite direction,” says the website.

“As things stand, it will be very difficult for either party to appeal to both Leave- and Remain-voting marginals at the same time, opening up the prospect of either a continuing stalemate or sweeping changes to the electoral map as voters base their allegiances less on traditional party loyalties,” the website adds.

24 June - May bows out

After failing three times to get her withdrawal agreement through Parliament, Theresa May set a resignation date of 7 June.

Speaking at a Downing Street podium, May said it had been “the honour of my life” to serve as PM. The visibly moved leader added she would leave “with no ill will, but with enormous and enduring gratitude to have had the opportunity to serve the country I love”.

24 July - the Johnson era beings

Boris Johnson entered Downing Street after winning the Conservative party leadership election with 66% of the vote, a comfortable victory over rival Jeremy Hunt.

In a remarkably prescient acceptance speech, Johnson said that even some of his own supporters may “wonder quite what they have done”.

He repeated his campaign commitments to “deliver Brexit, unite the country and defeat Jeremy Corbyn”.

Johnson quickly selected a cabinet packed with loyal Brexiteers, and appointed Vote Leave director Dominic Cummings as his most senior adviser.

28 August - Parliament put on ice

In August, reports emerged that the new PM had asked the Queen to suspend Parliament for five weeks in the run-up to 31 October.

Johnson claimed the progrogation was a routine move intended to pave for the way a Queen’s speech on 14 October setting out his government’s legislative programme, the BBC reported.

But most commentators agreed that the prorogation was scheduled to give MPs less time to try to block no-deal before the 31 October deadline.

Labour deputy leader Tom Watson described the move as an “utterly scandalous affront to our democracy”.

4 September 2019 - MPs take back control and BoJo demands general election

After voting to take control of Commons business for the day, MPs backed a bill blocking a 31 October no-deal Brexit.

Opposition MPs and Tory rebels joined forces to ensure the legislation passed by 327 votes to 299, the London Evening Standard reported.

Their victory meant that Johnson would have to ask for a Brexit extension beyond the 31 October Brexit deadline if he can’t secure a deal with the EU.

The PM - who has called the 31 October deadline “do or die” - reacted by calling for a general election.

But opposition parties collectively refused to back a general election vote until the legislation blocking a no-deal exit on Halloween had passed into law and the EU agreed the extension, says The Guardian.

24 September 2019 - Supreme Court brands prorogation ‘unlawful, void and of no effect’

In a landmark decision, the UK Supreme Court ruled that Boris Johnson’s five-week prorogation of Parliament in the run-up to the Brexit deadline was “unlawful”.

Announcing the judgment, Lady Hale said the case was a “one-off” that came about “in circumstances which have never arisen before and are unlikely to ever arise again”.

Amid calls to resign from opposition leaders, Johnson said he “profoundly disagreed” with the ruling but would “respect” it.

John Bercow, speaker of the Commons, said MPs needed to return to Parliament “in light of the explicit judgement”. They did so the following day.

2 October 2019 - Johnson sets out his ‘reasonable compromise’ Brexit deal

By early October, the PM had made a formal proposal to the EU setting out his alternative to the Irish backstop. He claimed his plan was “entirely compatible with maintaining an open border in Northern Ireland”, unlike the “bridge to nowhere” backstop.

The proposals would leave the UK in the same customs territory as the EU, and would keep Northern Ireland under EU regulations until a permanent trade deal was reached.

But there was “dismay behind the scenes in Brussels” after Johnson revealed his plans, according to The Guardian, with the EU’s chief negotiator Michel Barnier privately critical of the proposals.

6 October 2019 - reaching deal ‘essentially impossible’

Following a phone call between Johnson and Angela Merkel, a Downing Street source told journalists that a Brexit deal is “overwhelmingly unlikely”.

The No. 10 insider said that in a “clarifying moment”, the German chancellor insisted that the UK “cannot leave without leaving Northern Ireland behind in a customs union and in full alignment forever” - a situation that would never be acceptable to the EU.

And that meant a deal was “essentially impossible not just now but ever”, the source said.

19 October 2019 - the showdown

Parliament hosted a special session for MPs on Saturday 19 October - less than two weeks before the Halloween Brexit deadline.

It was the fifth time Parliament sat on a Saturday for 80 years, with the previous occasions including include the day before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Suez Crisis in 1956 and the Falklands War in 1982, says The Guardian.

Johnson was legally obliged by the Benn Act to send a letter to the EU on that date requesting a three-month Brexit extension after Parliament refused to pass his deal.

12 December 2019 – election day

After Parliament knocked back Johnson’s Brexit deal, the prime minister insisted the only way to “get Brexit done” would be to hold a general election and break the Parliamentary deadlock.

On 28 October, with no-deal taken off the table, Labour backed a government bill enabling a general election. Parliament was subsequently dissolved on 6 November, with the battle for No. 10 kicking off in earnest.

Polls put the Conservative lead at around 11 points throughout the campaign, but it was still a shock when the Tories romped home with an 80-seat majority on 12 December.

Johnson won Leave-voting seats from Labour across Wales, the north and the Midlands, including seats that had been Labour for 100 years - and had never been Tory.

Lib Dem leader Jo Swinson lost her seat to the SNP and stepped down, while Jeremy Corbyn said he would not fight another election as Labour leader after his party suffered its worst defeat since 1935.

31 January 2020 – departure day

Having won the majority he so desired in December, Johnson passes his withdrawal agreement, paving the way for the UK to leave the EU on 31 January.

All new Conservative MPs pledge support for Johnson’s deal, meaning that his 80-strong majority has no problem passing the agreement by 330 to 231.

For the first time in history, every devolved assembly - Holyrood, the National Assembly for Wales and Stormont - votes to reject the legislation.

Thousands of people convene in Parliament Square to commemorate the UK leaving the EU at 11pm.

1 February - transition period

An 11-month transition phase begins, running to 31 December 2020. Most arrangements remain the same until that date, but both London and Brussels face a race against time to finalise a deal on their future relationship.

2 March - first post-election meetings

David Frost and his EU counterpart Barnier, convene the first formal meeting for the negotiation of the future relationship between the UK and the EU, starting in Brussels and then alternating with London.

The first round of talks ends on 5 March with Barnier warning that there are “grave” differences in the visions of the UK and the EU. Later in March, planned talks are scrapped due to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic.

20 April - Covid summit

Talks resume after a lengthy break during which Johnson is hospitalised with coronavirus. On the table are the crucial issues of the future trade relationship, including security policy, trade rules and the contentious issue of fishing rights.

Talks end with Barnier appearing convinced that the UK is “running down the clock” in an attempt to force through a no-deal Brexit, stating: “The UK cannot refuse to extend the transition, and at the same time slow down discussions on important areas.”

15 May - progress halted

The most fractious talks to date take place, with Frost claiming that a far-reaching free trade agreement cannot be agreed before the end of the year “without major difficulties” after “very little progress” is made.

Barnier says he is “exhausted” with the UK's approach to talks, and his relationship with Frost deteriorates to a new low in late May when Frost accuses Barnier of treating the UK as an “unworthy” partner in a letter to Brussels.

8 June - fishing fallout

Downing Street’s hopes of a Brexit deal dim as Barnier loses control of talks on fishing rights. Frost hopes to discuss fishing quotas, but the European Commission is unable to go into detail because of opposition led by France.

30 June - deadline extension

The UK allows the deadline for formally applying for an extension to the transition period to pass, ramping up pressure on both sides to reach a deal before 31 December.

21 August - deal unlikely

Another round of negotiations ends with Barnier stating that securing a deal “seems unlikely”.

This time, the two sides fail to make progress over a long-standing disagreement over lorry drivers’ rights after Brexit, with Barnier expressing surprise over the UK debate about the loss of haulage rights after Brexit, while stressing that any future access would depend on accepting EU standards on hauliers’ working time and other regulations.

7 September - deal deadline

Johnson puts forward an ultimatum to negotiators saying the UK and Europe must agree a post-Brexit trade deal by 15 October or Britain will walk away without a deal.

The same day, Johnson throws a major spanner in the works by seeking to override parts of the previously agreed-upon Brexit withdrawal deal with his own UK internal markets bill, which will “eliminate the legal force of parts of the withdrawal agreement”.

8 September - Internal Markets Bill

The following day, in the wake of outrage from Brussels over the introduction of the bill, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Brandon Lewis, tells Parliament that by introducing the legislation, the UK government will “break international law in a very specific and limited way”.

The UK government is widely criticised for the move, with European Commissioner Maros Sefcovic telling Michael Gove that an adoption of the bill “would constitute an extremely serious violation of the Withdrawal Agreement and of international law”.

A statement from the European Commission says that the UK has “seriously damaged trust” between London and Brussels.

The EU threatens legal action over the decision, stating that it will “not be shy” in using “legal remedies to address violations of the legal obligations” contained in the Internal Market Bill.

9 September - ‘limited and specific’ law breaking

The internal markets bill is adopted.

1 October - EU legal action

The EU Commission confirms that it will launch legal action against the UK’s attempt to override parts of the Brexit withdrawal agreement.

European Commission head Ursula von der Leyen says that the UK has been put on formal legal notice over the bill, giving Boris Johnson until the end of September to scrap clauses that contradict parts of the original agreement.

“The deadline has lapsed,” Von der Leyen tells reporters. “We had invited our British friends to remove the problematic parts of their draft Internal Market Bill, by the end of September.”

7 October – cards on the table

The president of the European Council, Charles Michel, says it is “time for the UK to put its cards on the table” over a post-Brexit trade deal. Following a call with Michel, Downing Street said it had “reiterated that any deal must reflect what the British people voted for”.

15 October – Paris shocks London

Emmanuel Macron insists that London must back down in a row over fishing rights in order to get a Brexit deal. Downing Street says it is “startled” by the development, The Guardian reports.

16 October – Johnson backs away

Johnson says the UK should “go for the Australia solution” as he announced that it’s time to “get ready" for the prospect of no-deal Brexit.

Little more than a week after senior cabinet ministers said that Britain had a 66% chance of a trade agreement, the prime minister says the EU had “abandoned the idea of a free trade deal” and had “refused to negotiate seriously for much of the last few months”.

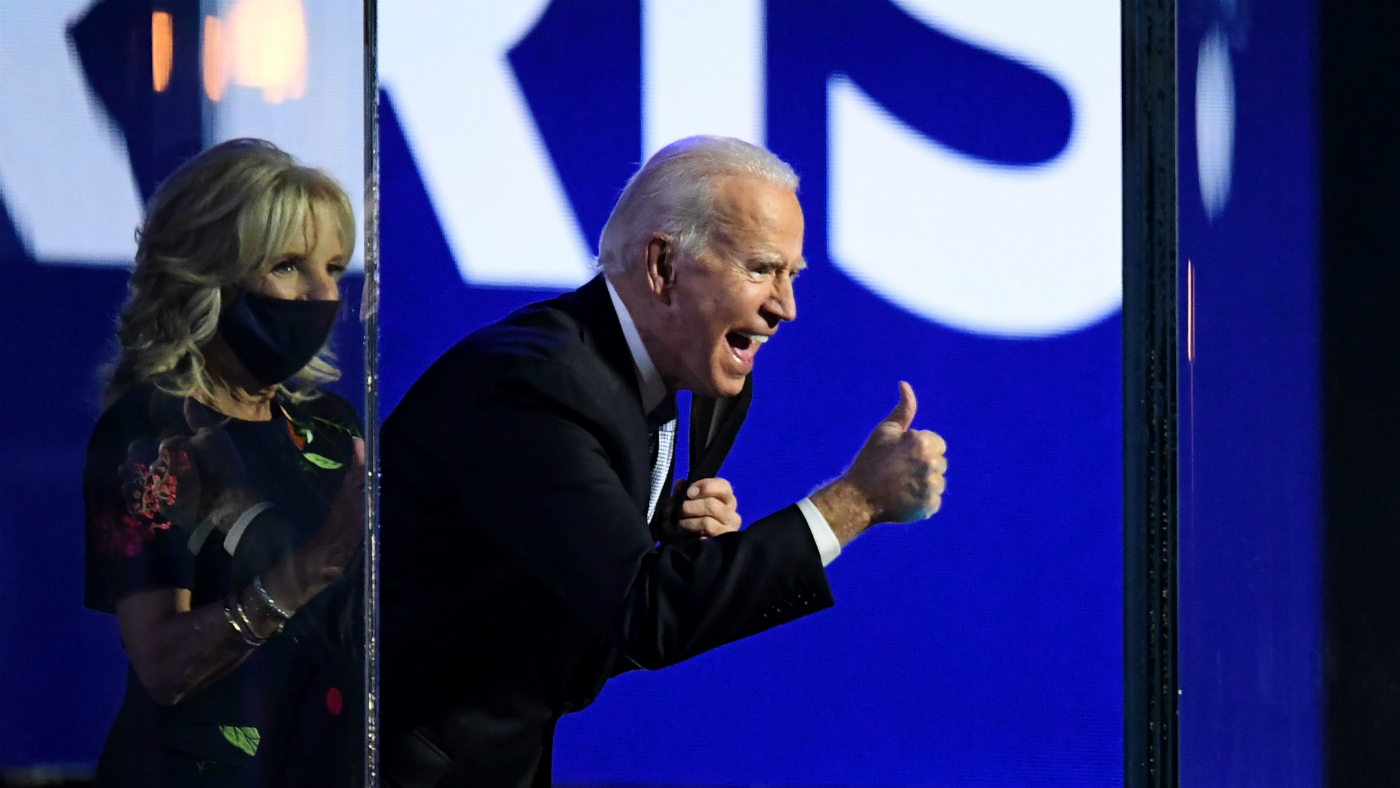

7th November - Biden wins the White House

Joe Biden beats Donald Trump to become president, but Johnson’s determination to press ahead with the Internal Market Bill is unabated.

During the campaign, president-elect Joe Biden said that “any trade deal between the US and UK must be contingent upon respect for the agreement and preventing the return of a hard border”.

Johnson has said proposed changes to legislation would not harm the Good Friday peace agreement.

9 November - House of Lords defeat

The government faces a major setback to its Brexit legislation when its Internal Market Bill suffered a heavy defeat in the House of Lords.

Peers overwhelmingly back removing a section of the bill that the government admitted would allow it to break international law. The Lords vote to remove this section of the bill by 433 votes to 165.

The government says it will reinstate the clauses when the bill returns to the House of Commons in December.

12 November

Talks resume, with the government claiming negotiations are in “the final stage” but that British negotiators needed to see "movement on the EU side”.

Cabinet minister Michael Gove tells the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg that the “penny is dropping” in Brussels over EU sovereignty.

"One of the arguments we have always made is that by choosing to leave the European Union we became a sovereign equal - and it’s absolutely important that the EU recognise that," Gove says.

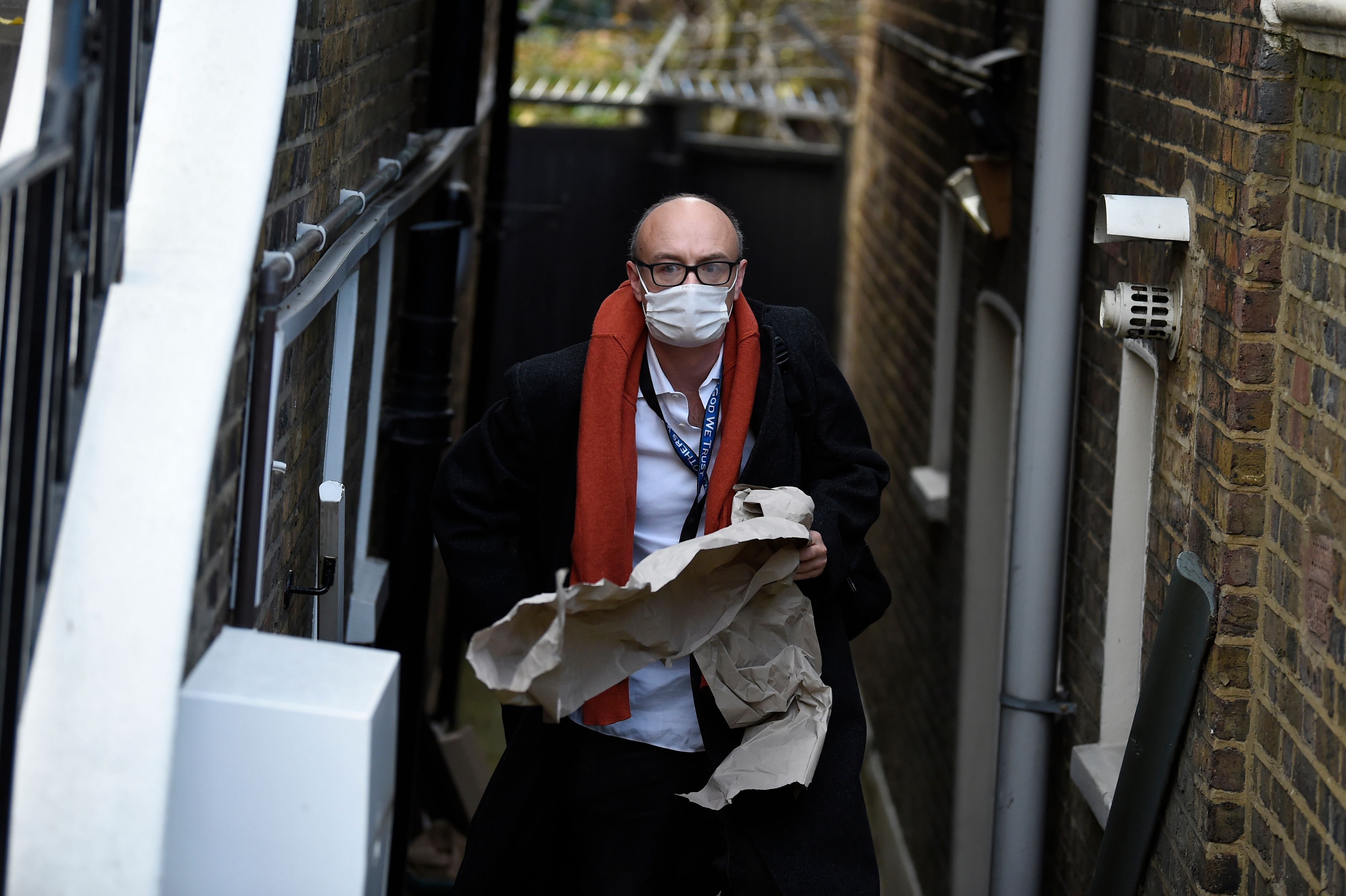

13 November - Cummings and goings

Dominic Cummings, a key figure in the Vote Leave campaign and a top aide to Boris Johnson, says he will leave his role by the end of the year.

24 November - full steam ahead?

Ireland’s prime minister predicts that a Brexit deal outline may be completed within days after Michel Barnier emerged from quarantine after testing positive for Covid-19. Taoiseach Micheal Martin (pictured above) says he is “hopeful that, by the end of this week, that we could see the outlines of a deal”. No-deal materialises.

26 November - no-deal blow

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicts that a no-deal Brexit would strike a devastating blow to parts of the UK economy spared the worst of the coronavirus crisis and result in hundreds of thousands of job losses.

A failure to reach a post-Brexit trade agreement with the EU could reduce GDP by a further 2% next year on top of the financial damage wrought by the pandemic, an OBR report says.

7 December - controversy in the Commons

MPs vote on House of Lords amendments to the Internal Market Bill that stripped out the international-law-breaking elements that would override the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement. MPs vote to reinstate the law breaking clauses.

10 December - final EU meeting

A big day in Brussels as the EU holds its final European Council summit of the year. The plan had been for the bloc to sign off any Brexit deal at this last meeting of 2020, but no deal has been agreed.

11 December - no-deal planning

The EU publishes its no-deal planning. Negotiations between the two sides “are still ongoing but the end of the transition is near”, von der Leyen tweets. “There is no guarantee that if and when an agreement is found it can enter into force on time... Today we present contingency measures.”

18 December - missed deadline

Another week, another missed Brexit deadline. Talks stall over fishing rights and the level-playing field as Boris Johnson tells the EU that a Brexit trade deal could be agreed within days provided the bloc changes its position on the two key outstanding issues. A new deadline is set by MEPs for 20 December.

20 December - deja vu

The deadline agreed by MEPs to agree a trade deal is missed. Talks continue.

23 December - stormy waters

Johnson and von der Leyen hold a series of “secret phone calls” this week, as negotiators try to thrash out a compromise on the “outstanding differences on fisheries”.

A senior source on the UK side tells The Sun that “there is a deal on the table now”, but Eurasia Group analyst Mujtaba Rahman says the UK’s most recent offer on fishing rights is “totally unacceptable” to EU negotiators.

24 December - white smoke

The UK and EU announce the agreement on a trade deal. Coming into effect on 1 January 2021, the deal will replace the existing arrangements under the transition period.

Parliament will need to ratify the agreement, however, MPs may be called back early from their Christmas break to vote on 30 December. A senior EU diplomat tells Reuters that a provisional application of the deal will need to be approved by the EU27 as there is not time for the EU parliament to ratify the deal.

“Arguments were sometimes fierce, but this is a good deal for the whole of Europe,” Johnson says. He adds that “although we have left the EU, this country will remain culturally, emotionally, historically, strategically, geologically attached to Europe”.

“We have finally found an agreement,” von der Leyen says. “It was a long and winding road. But we have got a good deal to show for it. It is fair. It is a balanced deal. And it is the right and responsible thing to do for both sides.”

Joe Evans is the world news editor at TheWeek.co.uk. He joined the team in 2019 and held roles including deputy news editor and acting news editor before moving into his current position in early 2021. He is a regular panellist on The Week Unwrapped podcast, discussing politics and foreign affairs.

Before joining The Week, he worked as a freelance journalist covering the UK and Ireland for German newspapers and magazines. A series of features on Brexit and the Irish border got him nominated for the Hostwriter Prize in 2019. Prior to settling down in London, he lived and worked in Cambodia, where he ran communications for a non-governmental organisation and worked as a journalist covering Southeast Asia. He has a master’s degree in journalism from City, University of London, and before that studied English Literature at the University of Manchester.