Is it time the UK decriminalised drugs?

Making personal use legal appears to have stopped Portugal's heroin epidemic, but there's a different story in the Czech Republic

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Britain's drug strategy has a clear aim: to "safeguard [the] vulnerable and stop substance misuse". But critics say its outdated methods fail to get to grips with the problem.

Announcing the new policy last week, Home Secretary Amber Rudd said Britain's "tough law enforcement response" to drug use "must go hand in hand with prevention and recovery" - in other words, the legal fight against drugs will be mixed with medical programmes to help addicts.

However, with Ireland, France, Portugal and others moving towards decriminalisation, the UK has become increasingly isolated in its approach.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"We are unique among modern democracies in maintaining an approach based on nothing but prohibition," Peter Reynolds, president of Clear Cannabis Law Reform, writes in City AM. "In fact, we now stand closer to countries such as Russia, China, Indonesia, and Singapore. The only thing that separates us from countries with such medieval policies is our lack of the death penalty for drug offences."

As more nations experiment with partial or total legalisation, Britain is likely to come under increasing pressure to justify laws that criminalise drug use.

Both the World Health Organisation and the UN have called for the repeal of laws "proven to have negative health outcomes" and which "counter established public health evidence", including laws which criminalise drug use or possession for personal use.

So, what can the UK learn from countries which take a radical approach to drug policy? Does decriminalisation actually reduce drug addiction, or merely keep it out of sight?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Britain doesn't have to look far for an alternative. In 2001, Portugal became the first country in the world to decriminalise all personal drug use.

Drug dealing, trafficking or possessing more than ten days' supply still remains a criminal offence, but users now appear before a "addiction dissuasion commission" made up of a health professional, a legal expert and a social worker. In theory, the panel has the power to impose punitive measures such as fines or bans on visiting certain places or people, but the vast majority of hearings end with a referral to addiction support services.

At the time, advocates hoped this approach would tackle Portugal's heroin epidemic - by the 1990s, one per cent of the population was addicted to the drug, NPR reports.

It appears they were right. Not only has the number of heroin addicts halved since then, but drug-related HIV infections have dropped from 1,016 cases to only 56 in 2012, thanks to drop-in centres that provide clean needles, syringe bins and condoms, Vice reports.

Decriminalisation has had other results - and not the effect some critics feared.

Data gathered by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) indicates loosening the drugs laws has not lead to increased experimentation with drugs or the normalisation of drug use.

A little more than five per cent of young people in Portugal reported using cannabis in the last year. In the UK, where cannabis is a Class B drug, it was 11.3 per cent. In addition, only 0.6 per cent of young adults in Portugal reported having used MDMA in the last year and 0.4 per cent for cocaine. Those figures are 3.1 per cent and four per cent respectively in the UK.

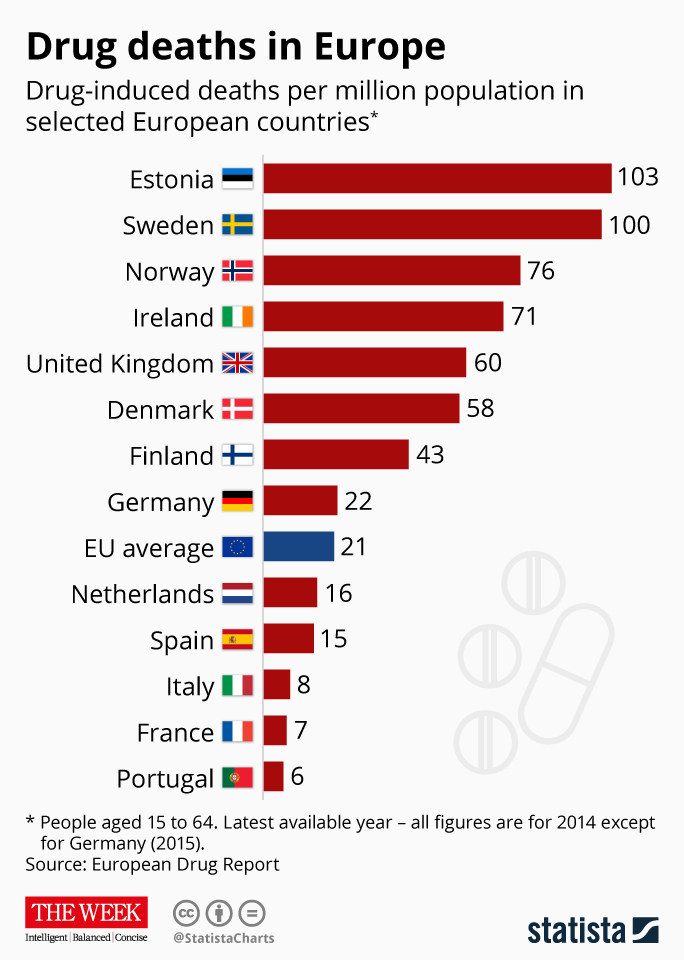

The difference in death rates related to drugs between the two countries is equally interesting.

Drug abuse is the fifth most common cause of preventable deaths in the UK, with 60.3 deaths per million in 2014 - almost three times the European average, says the EMCDDA.

By comparison, the Portuguese drug-induced mortality rate has more than halved since 2008 to reach 5.8 deaths per million in 2015.

Decriminalisation alone is not responsible for this, however. When Portugal introduced its reforms, "an important aspect of the plan was to divert the money used for the juridical system - arresting and imprisoning addicts - into treatment", says Al Jazeera.

Between 2001 and 2002, spending on prevention and outreach campaigns increased by €24.5 million and with no fear of arrest or imprisonment, addicts have been inclined to seek help for their problem.

However, the argument is not so cut and dry. The Czech Republic decriminalised possession of small quantities of drugs for personal use in 2009, but its rates of use and addiction have remained broadly similar to pre-decriminalisation.

Although "hard" drug use in the country is broadly in line with the rest of Europe and overdose deaths remain low, almost one in five young Czechs reported using cannabis in the previous year, the third highest in Europe after France and Italy.

In addition, the homemade methamphetamine pervitin, which is injected, has become the "main substance linked to problem drug use" in the republic, according to the EMCDDA.

So what - if anything - can the UK learn? The primary takeaway is that decriminalisation in these cases has not led to higher rates of drug abuse and has actually had the opposite effect in Portugal.

However, just as important is the understanding that while legal reforms reduce the social stigma and fear of prosecution that can prevent addicts from seeking help, the extent and quality of that help is the key to tackling addiction and cutting the number of lives lost to drug abuse.

Infographic by www.statista.com for TheWeek.co.uk

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

4 Americans kidnapped in Mexico by armed gunmen, 2 killed, FBI says

4 Americans kidnapped in Mexico by armed gunmen, 2 killed, FBI saysSpeed Read

-

The Week Unwrapped: Seeing stars, prescribing comedy and decriminalising drugs

The Week Unwrapped: Seeing stars, prescribing comedy and decriminalising drugspodcast What will the James Webb Telescope accomplish? Why is the NHS sending people to comedy courses? And are drugs laws about to change in the British capital?

-

‘France wouldn’t be France without strikes, protests and police baton charges’

‘France wouldn’t be France without strikes, protests and police baton charges’Instant Opinion Your digest of analysis and commentary from the British and international press

-

Why codeine deaths have reached a record high

Why codeine deaths have reached a record highfeature Rise of the ‘dark web’ and demography of addicts may explain surge

-

‘Boris Johnson’s natural liberalism doesn’t extend to drugs’

‘Boris Johnson’s natural liberalism doesn’t extend to drugs’Instant Opinion Your digest of analysis and commentary from the British and international press

-

The benefits of cannabis legalisation

The benefits of cannabis legalisationIn the Spotlight London Mayor Sadiq Khan says there is widespread public support for decriminalisation of the class-B drug

-

Cathedral livestreams memorial service for stray cat

Cathedral livestreams memorial service for stray catSpeed Read And other stories from the stranger side of life

-

The Week Unwrapped podcast: Sporting genes, Colombia and orcas

The Week Unwrapped podcast: Sporting genes, Colombia and orcasIn Depth What does Caster Semenya’s latest defeat say about gender? Is Colombia slipping into conflict? And are killer whales turning against us?