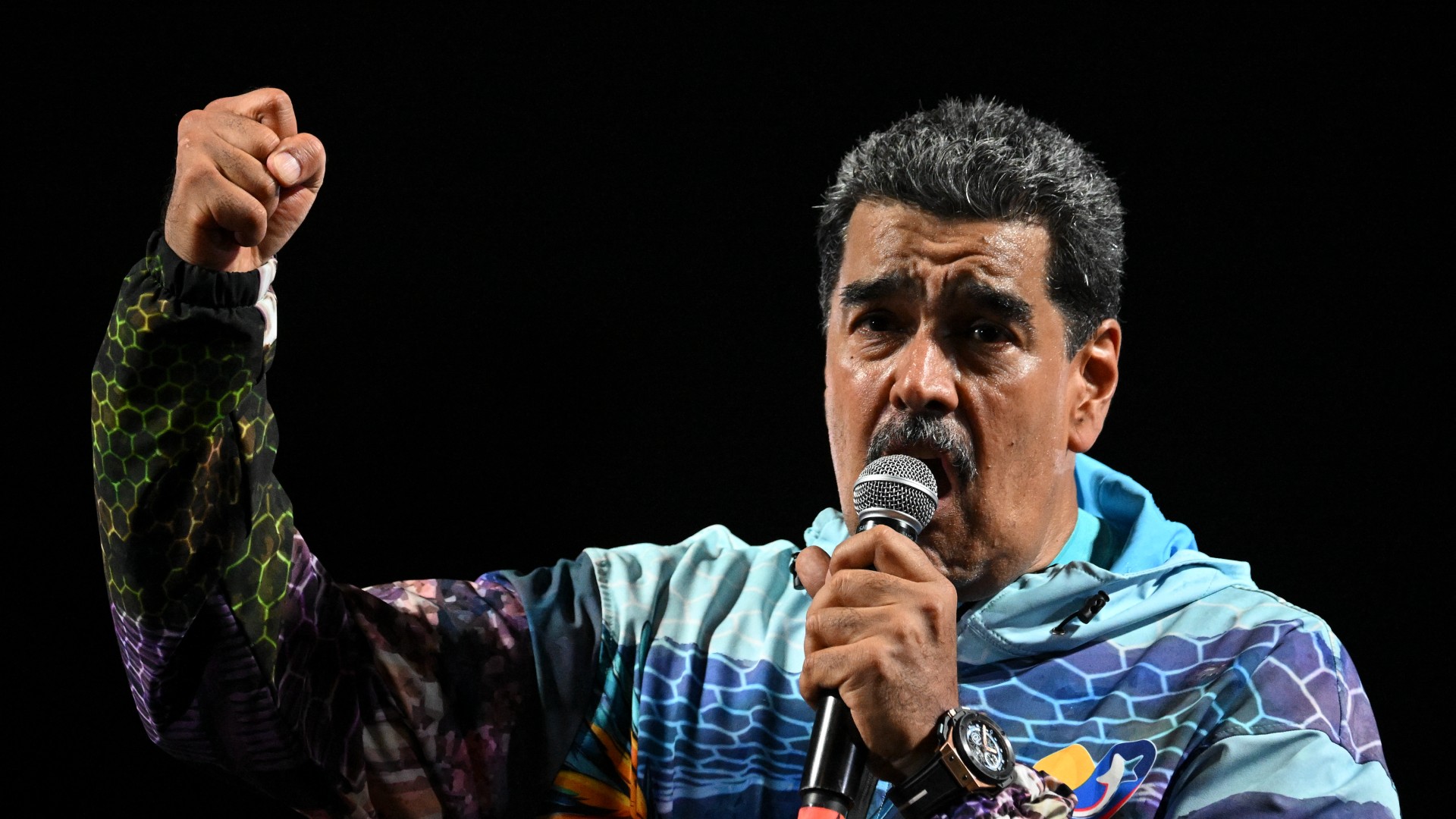

Venezuela election: first vote in a decade offers hope to poverty-stricken nation

Nicolás Maduro agreed to 'free and fair' vote but poor polling and threat of prosecution pushes disputed leader to desperate methods

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the US agreed to normalise relations with Venezuela, it was on the proviso that Nicolás Maduro would hold "free and fair elections".

The authoritarian president, who inherited power from the late revolutionary Hugo Chávez in 2013 and whose re-election in 2018 was widely condemned as fraudulent, is not recognised as legitimate by most of the world. The Trump administration responded to the sham elections with harsh sanctions on Maduro and the oil-rich yet desperately poor South American nation.

But an agreement last October, which allowed Joe Biden to lift most of the sanctions, may give Venezuelans the chance to vote a deeply unpopular incumbent out of the Miraflores Palace on 28 July.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How is the election campaign going?

After years of negotiation, the Maduro regime and the opposition signed a US-backed agreement in October to hold a fair election. But authorities disqualified hugely popular opposition leader María Corina Machado, who had won more than 90% of the vote in the primaries, on "trumped-up grounds", said The Economist. The government-allied Supreme Court upheld the ban in January, which led the US to reimpose most sanctions.

Machado has since "ceded all her political capital" to proxy Edmundo González Urrutia, a 74-year-old diplomat who "until now had moved behind the scenes of power", said El País, and now leads in the polls by 20 to 30%.

This has "prompted Maduro to launch a charm offensive", said the Financial Times, appearing on TikTok and at rallies "with a spry, avuncular persona". A leader responsible for "economic disaster" now presents himself as a "relatable everyman" from the barrio, who "dances, poses for selfies and sings for his audience".

For the first time since 2013, the Maduro government "looks scared", said Foreign Policy. "It fears democracy," wrote Christopher Sabatini, senior research fellow for Latin America at Chatham House. About two-thirds of Venezuelans say they would support any opposition candidate against Maduro. "Stealing this contest won't be as easy as it was for Maduro in 2017, 2018 or 2020."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Will they be 'free and fair' elections?

The regime's internal polling shows that in a fair vote, Maduro would be "totally doomed", a source told The Economist. But he "appears determined to cling to power – through intimidation".

At least 37 opposition activists have been arrested this year, and 10 elected mayors who supported González have been ousted. Maduro also withdrew an invitation to the EU to send a delegation of election observers.

Only 69,000 out of at least 3.5 million eligible Venezuelans abroad were able to register to vote, due to cumbersome bureaucracy and expense, according to rights groups. The "vast majority" would have voted for the opposition, said the FT.

Maduro controls most state institutions, including the courts, the electoral authorities, the army and much of the media – "not to mention violent paramilitary gangs", said The New York Times (NYT). There is "widespread doubt" that he would accept or even publicise an opposition victory.

That's if the election even happens. The prospect of postponing the ballot is being "openly talked about", said El País. A manufactured incident in the ongoing territory dispute with neighbouring Guyana, or a purported threat to Maduro's life, could provide the pretext.

What are the stakes?

Maduro's tenure has been marked by economic collapse, growing authoritarianism and the largest exodus of people in Latin American history. Nearly eight million Venezuelans – more than a quarter of the population – have fled since 2014.

Over the past decade, GDP has declined by about 73%, said Reuters. Venezuela suffers the second-highest level of hunger in South America, and, for the 10th consecutive year, the highest inflation in the world. This election, the "dire straits in which many live" will be "top of people's minds".

If Maduro claims victory, Venezuela will "remain paralysed", said El País. A second hostile Trump presidency would "complicate things even further".

That could also have a knock-on effect on the US elections. More than half of migrants crossing the Darién Gap into the US are Venezuelan, which has already become a "dominant theme" in campaigns, said the NYT.

If González wins, experts believe millions could return home, but if Maduro clings to power, "even more will be tempted to head to the US border", said CNN.

In the US, Maduro still faces criminal charges of "human rights abuse, corruption and involvement in the narcotics trade", said the FT. If Maduro does give up power, it would almost certainly be with a deal that would shield him from prosecution.

Also at stake is the future of Venezuela's oil reserves – the largest in the world – and the strength of its alliances with China, Russia and Iran. Those authoritarian nations have "already embedded efforts to expand their economic and political presence in Venezuela and the hemisphere", said Sabatini. Russia will be "doing everything it can to scuttle international interests in a free and fair election".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa scheme

The UK expands its Hong Kong visa schemeThe Explainer Around 26,000 additional arrivals expected in the UK as government widens eligibility in response to crackdown on rights in former colony

-

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’

‘Hong Kong is stable because it has been muzzled’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?

How are Democrats trying to reform ICE?Today’s Big Question Democratic leadership has put forth several demands for the agency

-

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election win

Japan’s Takaichi cements power with snap election winSpeed Read President Donald Trump congratulated the conservative prime minister

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

Trump links funding to name on Penn Station

Trump links funding to name on Penn StationSpeed Read Trump “can restart the funding with a snap of his fingers,” a Schumer insider said

-

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firings

Trump reclassifies 50,000 federal jobs to ease firingsSpeed Read The rule strips longstanding job protections from federal workers

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court