What Donald Trump owes the Christian Right

Conservative Christians played an important role in Trump’s re-election, and he has promised them great political influence

Conservative Christians backed Donald Trump's presidential campaign solidly and vociferously; many even suggested that he had been chosen by God. Weeks before the vote, Franklin Graham, son of Billy and one of America's most famous preachers, prayed aloud for him to win the election at a Trump rally in North Carolina while supporters cried: "Jesus! Jesus! Jesus!".

The TV evangelist Hank Kunneman described the election as "a battle between good and evil", adding: "There's something on President Trump that the enemy fears: it's called the anointing." Another celebrity evangelist, Lance Wallnau, prophesied his victories, describing them as "part of God's plan to usher in a new era of Christian dominion around the world".

Trump, for his part, has embraced the role. Referring to his attempted assassination in July, he declared on election night: "Many people have told me that God spared my life for a reason, and that reason was to save our country and to restore America to greatness."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How important was their support?

Very. About 13% of Americans are white white evangelical Protestants, and they have been a crucial section of the Republican Party's political base since the 1960s (black evangelicals, by contrast, tend to support the Democrats). White conservative Christians in general tend strongly to lean Republican, and their support has recently become more pronounced as the demographics of the US have changed. (According to Robert P. Jones of the Public Religion Research Institute, polls suggest that the Republican Party is now "70% white and Christian", and the Democratic party is "only a quarter white and Christian".)

The strong backing given to Trump by white Christians was a bedrock of his recent victory. According to the official exit polls, 82% of white evangelicals backed Trump, along with 63% of white Catholics and similar numbers of white non-evangelical Protestants.

Isn't Trump an odd choice for religious voters?

As a divorcee, a philanderer and a convicted felon, perhaps he is. He's not a regular churchgoer, either, though in recent years he has identified himself as a "true believer" (and a "non-denominational Christian"). Politically, though, he has promised to champion Christianity. In his first term, he made good on his promise to appoint conservative Christians to the Supreme Court; this led to the overturning of Roe v. Wade, which had protected the right to abortion. He has also often played up fears of a cultural takeover by the Left that would undermine Christian values. "They want to tear down crosses where they can, and cover them up with social justice flags," he has said. He has pledged to tackle "anti-Christian bias", and "to bring back Christianity in this country".

What does he mean by that?

It has been taken as an endorsement of "Christian nationalism": a broad movement based on the belief that the United States is a country founded by and for Christians, and that Christianity is under attack in modern America.

Christian nationalists demand a bigger role for the religion in the government of the US (although the First Amendment prohibits the government from establishing a state religion). They see being a Christian as an essential part of being a "real American". Such beliefs have permeated large swathes of government across the US, from school boards to state legislatures.

How influential are such beliefs?

Recent surveys suggest that only about 10% of the population are committed Christian nationalists; according to Pew Research, a majority of Americans support the separation of Church and state, but think the US should be informed by Christian values. Critics worry that Christian nationalism nevertheless may form a threat to democracy, because its fusion of theology and right-wing politics has become so influential in the Maga movement: as America becomes less white and less Christian, a minority cling fiercely to the idea that it is a divinely ordained promised land for European Christians. There is evidence, for instance, that some 6 January rioters were inspired by Christian nationalism.

What will Trump do for conservative Christians?

He has promised to "bring back prayer" in schools (until recently prayer was deemed unconstitutional in some circumstances); and to create a federal task force to fight anti-Christian bias. He says he will affirm that God made only two genders, male and female. And he will give enhanced political access to conservative Christian leaders. "It will be directly into the Oval Office – and me," Trump told pastors in Georgia in early November.

He has, though, pushed back against some demands from the evangelical movement: he has distanced himself from the prospect of a federal ban on abortion, saying that he supports leaving the issue to individual states. Perhaps most significant, though, will be the appointments of conservative Christians to important roles.

Which appointments?

He has selected Mike Huckabee, a former Southern Baptist pastor, as ambassador to Israel. Huckabee, like many in the evangelical movement, believes the US has a divine mandate to protect Israel. "Without any apology, I believe those who bless Israel will be blessed, those who curse Israel will be cursed," he has said.

Pete Hegseth, Trump's pick for secretary of defence, is an avowedly militant Christian, who has the Crusader battle cry "Deus vult", meaning "God Wills It" tattooed on his bicep, and wants to create a network of Christian schools so as to provide the "recruits" for an army that will eventually launch an "educational insurgency" to take over the nation. Probably most influential, though, are the religious conservatives, such as Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, whom Trump has already appointed to the Supreme Court.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

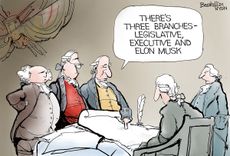

Today's political cartoons - December 20, 2024

Today's political cartoons - December 20, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - founding fathers, old news, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Parker Palm Springs review: decadence in the California desert

Parker Palm Springs review: decadence in the California desertThe Week Recommends This over-the-top hotel is a mid-century modern gem

By Catherine Garcia, The Week US Published

-

The real story behind the Stanford Prison Experiment

The real story behind the Stanford Prison ExperimentThe Explainer 'Everything you think you know is wrong' about Philip Zimbardo's infamous prison simulation

By Tess Foley-Cox Published

-

Does Trump have the power to end birthright citizenship?

Does Trump have the power to end birthright citizenship?Today's Big Question He couldn't do so easily, but it may be a battle he considers worth waging

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

Trump, Musk sink spending bill, teeing up shutdown

Trump, Musk sink spending bill, teeing up shutdownSpeed Read House Republicans abandoned the bill at the behest of the two men

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Is Elon Musk about to disrupt British politics?

Is Elon Musk about to disrupt British politics?Today's big question Mar-a-Lago talks between billionaire and Nigel Farage prompt calls for change on how political parties are funded

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Will California's EV mandate survive Trump, SCOTUS challenge?

Will California's EV mandate survive Trump, SCOTUS challenge?Today's Big Question The Golden State's climate goal faces big obstacles

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

'Underneath the noise, however, there's an existential crisis'

'Underneath the noise, however, there's an existential crisis'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

Failed trans mission

Failed trans missionOpinion How activists broke up the coalition gay marriage built

By Mark Gimein Published

-

Is the United States becoming an oligarchy?

Is the United States becoming an oligarchy?Talking Points How much power do billionaires like Elon Musk really have?

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

'It's easier to break something than to build it'

'It's easier to break something than to build it'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published