Parsons Green: Do we have a teenage jihadi problem?

Four of the six people arrested over tube train bombing are under 25

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A 17-year-old from south London is the latest person to be arrested in connection with the Parsons Green tube train bombing, bringing the number of those in police custody to six - all male, and four of them under the age of 25. None have yet been charged.

The youth of the suspects raises the question of whether the UK is becoming a breeding ground for teenage jihadis and, if so, is there a solution?

Is the number of radicalised young people rising?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

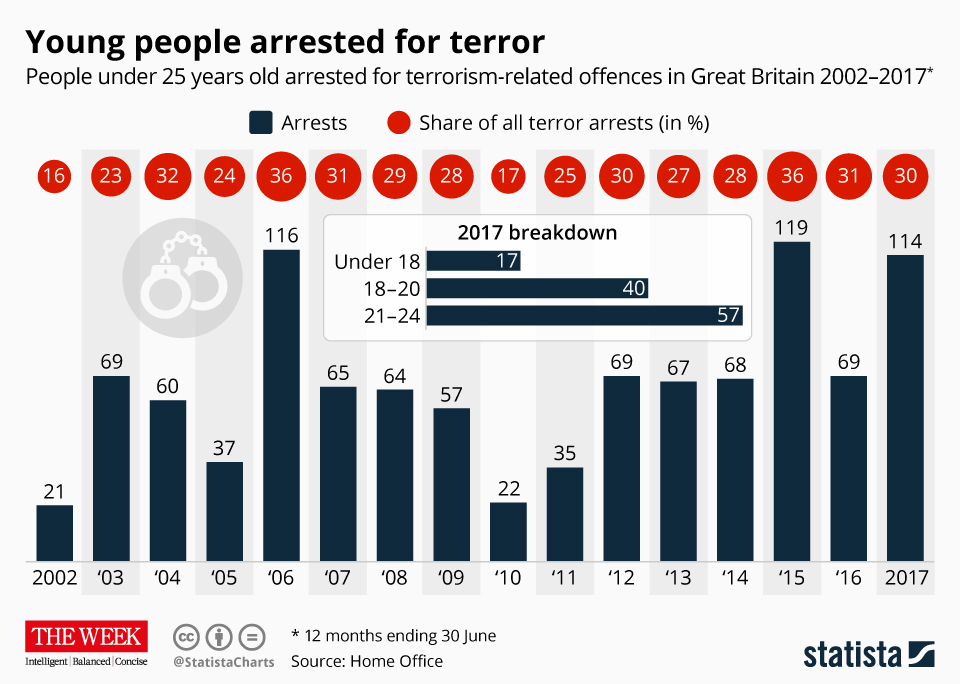

There were 117 people under 25 arrested for terrorist offences in the year ending 30 June 2017, according to the Home Office. Seventeen were under 18, 40 were aged 18-20 and 57 were aged 20-25.

Many of the arrests did not lead to charges, and the suspects were released - but convictions among young people for terror crimes have climbed in the last decade.

Nine Britons aged 25 or under were convicted of terror offences in the year ending 30 June 2017, and 19 were convicted in the previous year. In comparison, over a three-year period from 2008 to 2011, a total of only eight people aged 25 or under were convicted of terrorist crimes, according to Home Office statistics.

Why are extremist groups alluring?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

“One contributing factor might be a concept drawn from the world of cultural psychiatry: acculturation – the process of balancing two competing cultural influences,” The Guardian reports.

“Trying to meet the cultural expectations of parents while trying to fit in with peers, dealing with experiences of racism and balancing religious and western values ... poses a challenge for many Muslim youths living in western countries today,” The Guardian says.

Shiraz Maher of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation at King’s College London says extremist groups may offer of an identity for confused teens.

“The West doesn’t really know what it stands for; we don’t have anything to offer people to buy into and be part of,” says Maher.

He adds: “By contrast, Islamic State is self-assured; it’s very certain about what it stands for. It offers very powerful things to people who feel increasingly confused about hyphenated identities: am I British-Muslim? Am I British-Pakistani?

“Isis says: we can transcend all of that; we offer you an ideological and intellectual identity. You’re a Muslim; you’re part of the Ummah.”

How are teens recruited?

Part of the problem is the ease of accessing information on the internet. Online jihadist propaganda attracts more clicks in the UK than any other country in Europe, according to a study by UK think tank Policy Exchange.

Britain is the fifth-biggest audience in the world for extremist content after Turkey, the US, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

“The spate of terrorist attacks the UK suffered in the first half of 2017 confirmed that online extremism is a real and present danger,” the Policy Exchange study concluded. “In each case, online radicalisation played some part in driving the perpetrators to violence.”

What’s the solution?

More than 100 “how to make a bomb” manuals and recruitment videos are posted online in an average week, The Guardian says. Jihadists used Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to spread 27,000 extremist posts in just five months this year, The Sun reports.

Prime Minister Theresa May challenged Facebook, Google and other internet companies this week to go “further and faster” by removing jihadist material within two hours, the BBC and others said.

Max Hill QC, Britain’s official reviewer of terrorism laws, believes it is “entirely right that the spotlight should fall” on the tech companies but stops short of supporting new legislation that would require them to act.

“In Germany there was a proposal to levy heavy fines on tech companies whenever they failed to take down extremist content. I am not sure that is absolutely necessary,” Hill told The Guardian. “It is a question of the bulk of the material rather than a lack of co-operation in dealing with it.”

Instead of just focusing on social media giants, we should pay attention to those who access extremist materials - at an early stage.

The Policy Exchange report suggests many Britons would support new laws criminalising the reading of content that glorifies terror, similar to the laws on child pornography. Under the Terrorism Act 2000, it is an offence to possess information that could assist a would-be terrorist, but not material that glorifies terrorism.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

How the ‘British FBI’ will work

How the ‘British FBI’ will workThe Explainer New National Police Service to focus on fighting terrorism, fraud and organised crime, freeing up local forces to tackle everyday offences

-

How the Bondi massacre unfolded

How the Bondi massacre unfoldedIn Depth Deadly terrorist attack during Hanukkah celebration in Sydney prompts review of Australia’s gun control laws and reckoning over global rise in antisemitism

-

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?Today’s Big Question Deadly Bondi Beach attack the result of ‘permissive environment’ where warning signs were ‘too often left unchecked’

-

Ten years after Bataclan: how has France changed?

Ten years after Bataclan: how has France changed?Today's Big Question ‘Act of war’ by Islamist terrorists was a ‘shockingly direct challenge’ to Western morality

-

Arsonist who attacked Shapiro gets 25-50 years

Arsonist who attacked Shapiro gets 25-50 yearsSpeed Read Cody Balmer broke into the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion and tried to burn it down

-

Manchester synagogue attack: what do we know?

Manchester synagogue attack: what do we know?Today’s Big Question Two dead after car and stabbing attack on holiest day in Jewish year

-

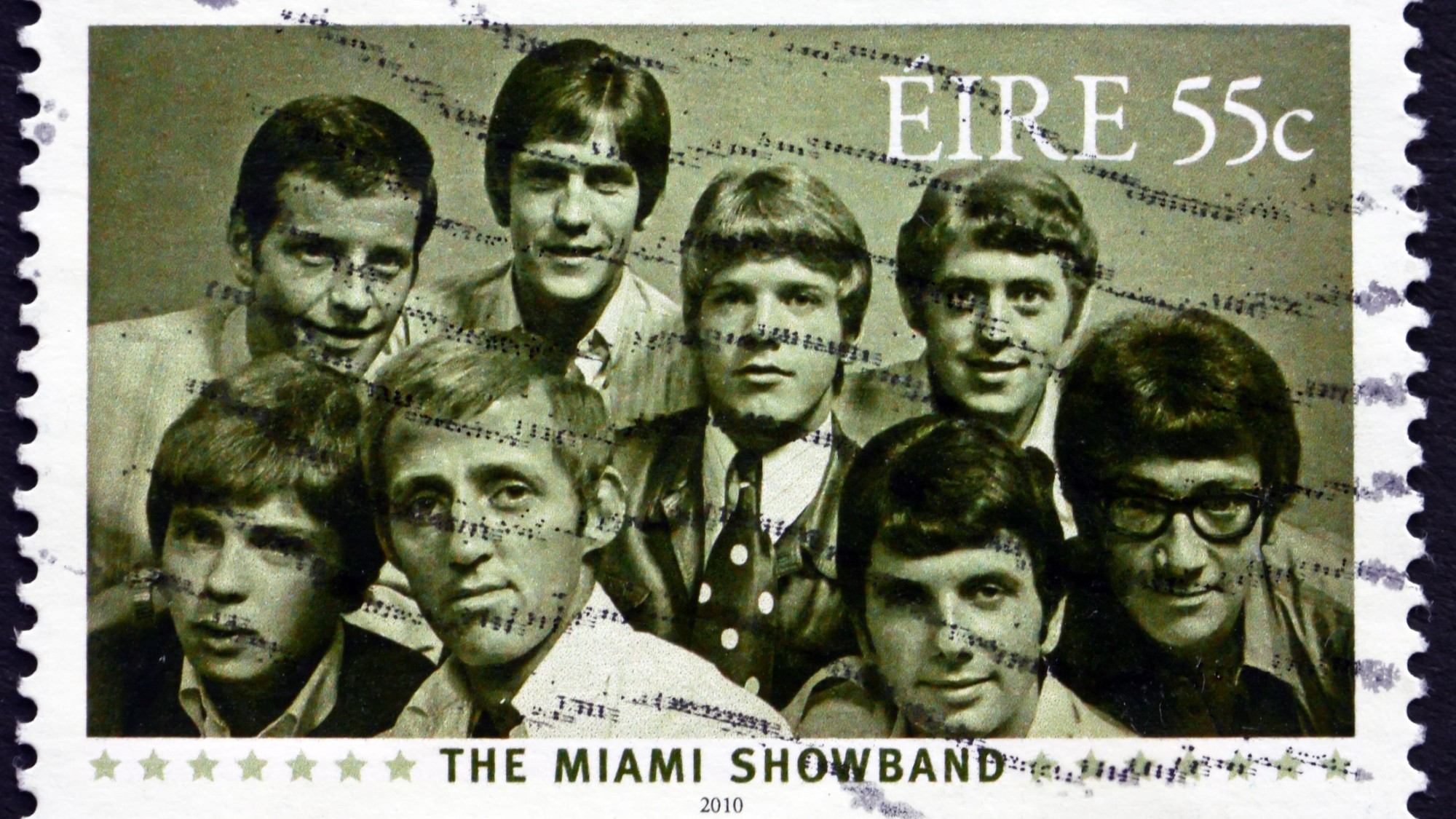

The Miami Showband massacre, 50 years on

The Miami Showband massacre, 50 years onThe Explainer Unanswered questions remain over Troubles terror attack that killed three members of one of Ireland's most popular music acts

-

The failed bombings of 21/7

The failed bombings of 21/7The Explainer The unsuccessful attacks 'unnerved' London and led to a tragic mistake