In 2050, Chinese politicians will talk about India the way Donald Trump talks about China

Just give it a few decades. It may well happen.

Imagine a Chinese version of Donald Trump blathering about his readiness to stomp all over India and make China great again.

Give it a few decades. It may well happen.

America has lost a lot of jobs to China — about 1.5 million manufacturing jobs from 1990 to 2007. And no one wails on this point over and over quite like Donald Trump.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But China won't be China forever. Its manufacturing boom also helped China's mammoth population surge into the global middle class. As China's per capita wealth continues to grow and it shifts into a service economy, the world's manufacturing jobs will start moving to India, Africa, and other parts of Asia.

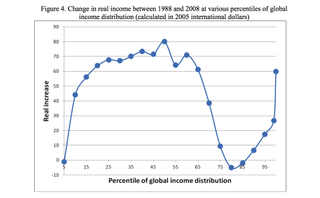

To see how this might play out, in terms of the overall global forces at play, we can look at data put together by economist Branko Milanovic. Below is a chart on how global incomes changed between 1988 and 2008. Imagine the x-axis is everyone in the world lined up, in order of how rich they were in 1988, from left to right. The y-axis is how much their incomes increased over the time period since.

Now, you see that divot on the right-hand side, between the 75th and 85th percentiles? That batch of poor souls whose real incomes actually went down over the last two decades? That's the working class in advanced Western countries. It's Americans who support Trump. It's also Europeans who support the rising anti-immigrant, anti-trade nationalist parties in their own countries. As Matt O'Brien put it at The Washington Post, that chart is something of a Rosetta Stone for understanding the political unrest here in the Western world.

But O'Brien also suggested something more hopeful: that our loss of jobs to China was basically a one-off event.

In the case of America, that may well be true. As countries develop, their populations become richer and are able to provide more demand internally, and that powers the economic shift from relying on manufacturing to relying on services. And since goods are a lot easier to export than services, it's also much easier for manufacturing industries to go running around the globe, chasing the poorest — and thus the cheapest — populations of workers. (Though it's worth wondering how many services may become exportable in the digital era.)

America has already gone through this process. Our manufacturing jumped up and left for China. Over there, the manufacturing-to-services shift is still underway, but is at its turning point. So where do the manufacturing jobs go next?

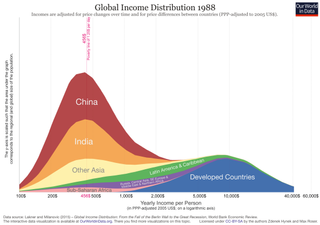

Here are some more charts that economist and data visualizer extraordinaire Max Roser created, based off data Milanovic put together with Christoph Lanker. The x-axis is level of income, the y-axis is population. Here's 1988:

And here's 2011:

You can go to Roser's website to see the whole presentation, but I'm sure you get the point: China moved decisively into the global middle class over this time period, but India, Africa, and the rest of Asia are still coming up. As they do, the manufacturing jobs will likely jump from China to them.

Enter Chinese Donald Trump to capitalize on the anger of China's working class.

But there may be a way to avoid it. China has been running a big trade surplus with America, exporting more than it imports. (America, in turn, has been running a trade deficit with China — and everyone else.) But that's actually the reverse of how textbook economics says it should happen. Developing countries are supposed to buy goods and borrow from rich countries as they build up their own economies.

The thing is, this textbook process requires the developing country to provide demand for its own economy internally. And that requires egalitarian distributions of income, so that everyone in the developing country can consume. But China is super unequal. And to stay unequal, the Chinese government depressed its currency, which allowed it to bleed demand from America, and create its jobs that way instead.

Meanwhile, that loss to our internal demand made it harder for America to generate jobs here. The problem wasn't so much that America lost manufacturing jobs per se, but that nothing else came along to replace the role they filled in our society. And American elites have been basically fine with this situation, since they benefit from inequality here as much as Chinese elites benefit from inequality over there.

And that illustrates the way out: The trade relationship between America-the-rich-country and China-the-developing-country has been deeply unhealthy for both sides. Once China becomes the rich country, maybe it can do better with India and Africa and the rest as they develop.

And that could help us all avoid Chinese Donald Trump.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

America's academic brain drain has begun

America's academic brain drain has begunIN THE SPOTLIGHT As the Trump administration targets universities and teachers, educators are eying greener academic pastures elsewhere — and other nations are starting to take notice

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Why is Musk targeting a Wisconsin Supreme Court race?

Why is Musk targeting a Wisconsin Supreme Court race?Today's Big Question His money could help conservatives, but it could also produce a Democratic backlash

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

How to pay off student loans

How to pay off student loansThe explainer Don't just settle for the default repayment plan

By Becca Stanek, The Week US Published

-

'Like a sound from hell': Serbia and sonic weapons

'Like a sound from hell': Serbia and sonic weaponsThe Explainer Half a million people sign petition alleging Serbian police used an illegal 'sound cannon' to disrupt anti-government protests

By Abby Wilson Published

-

The arrest of the Philippines' former president leaves the country's drug war in disarray

The arrest of the Philippines' former president leaves the country's drug war in disarrayIn the Spotlight Rodrigo Duterte was arrested by the ICC earlier this month

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

Ukrainian election: who could replace Zelenskyy?

Ukrainian election: who could replace Zelenskyy?The Explainer Donald Trump's 'dictator' jibe raises pressure on Ukraine to the polls while the country is under martial law

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Why Serbian protesters set off smoke bombs in parliament

Why Serbian protesters set off smoke bombs in parliamentTHE EXPLAINER Ongoing anti-corruption protests erupted into full view this week as Serbian protesters threw the country's legislature into chaos

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Who is the Hat Man? 'Shadow people' and sleep paralysis

Who is the Hat Man? 'Shadow people' and sleep paralysisIn Depth 'Sleep demons' have plagued our dreams throughout the centuries, but the explanation could be medical

By The Week Staff Published

-

Why Assad fell so fast

Why Assad fell so fastThe Explainer The newly liberated Syria is in an incredibly precarious position, but it's too soon to succumb to defeatist gloom

By The Week UK Published

-

Romania's election rerun

Romania's election rerunThe Explainer Shock result of presidential election has been annulled following allegations of Russian interference

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Russia's shadow war in Europe

Russia's shadow war in EuropeTalking Point Steering clear of open conflict, Moscow is slowly ratcheting up the pressure on Nato rivals to see what it can get away with.

By The Week UK Published