What was the Peterloo Massacre?

Manchester marks 200th anniversary of slaughter of protesters seeking parliamentary reform

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Commemorations are taking place across England this week to mark the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, one of the most controversial events in British political history.

On 16 August 1819, tens of thousands of peaceful protesters were charged by an armed cavalry as they gathered in Manchester’s St Peter’s Field to demand democratic reform. An estimated 18 people, including children, were killed, and hundreds more injured.

Earlier this week, Manchester City Council unveiled a £1m memorial to the atrocity - but in a more contemporary clash between the public and the authorities, was immediately accused of a “PR own goal”, The Guardian reports.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The monument, made up of concentric circles that can be used as steps by visitors, drew criticism earlier this year after disability rights groups pointed out it would be inaccessible to wheelchair users. Campaigners had anticipated that a new version would be unveiled on Friday, exactly two centuries after the massacre, but have been left outraged after construction workers quietly installed the original in “a deserted square in Manchester city centre” on Tuesday, says the newspaper.

In what organisers hope will prove a more successful tribute, crowds will gather at Manchester Central this weekend for an event dubbed From The Crowd, which will weave together “eyewitness accounts of those present at Peterloo 1819 with the words of contemporary protesters and poets”, says the Manchester Evening News.

What happened at the 1819 protest?

In the aftermath of the economically devastating Napoleonic Wars, which ended in 1815, the UK fell into a deep industrial depression. As food prices and unemployment soared, anger and unrest swept across the nation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

By 1819, the simmering tension had boiled over into mass protests, with demonstrators demanding expanded suffrage - fewer than 2% of the population had the vote - and the repeal of the disastrous “Corn Laws”, a series of tariffs and trade restrictions on imported grains that made bread unaffordable for many working people.

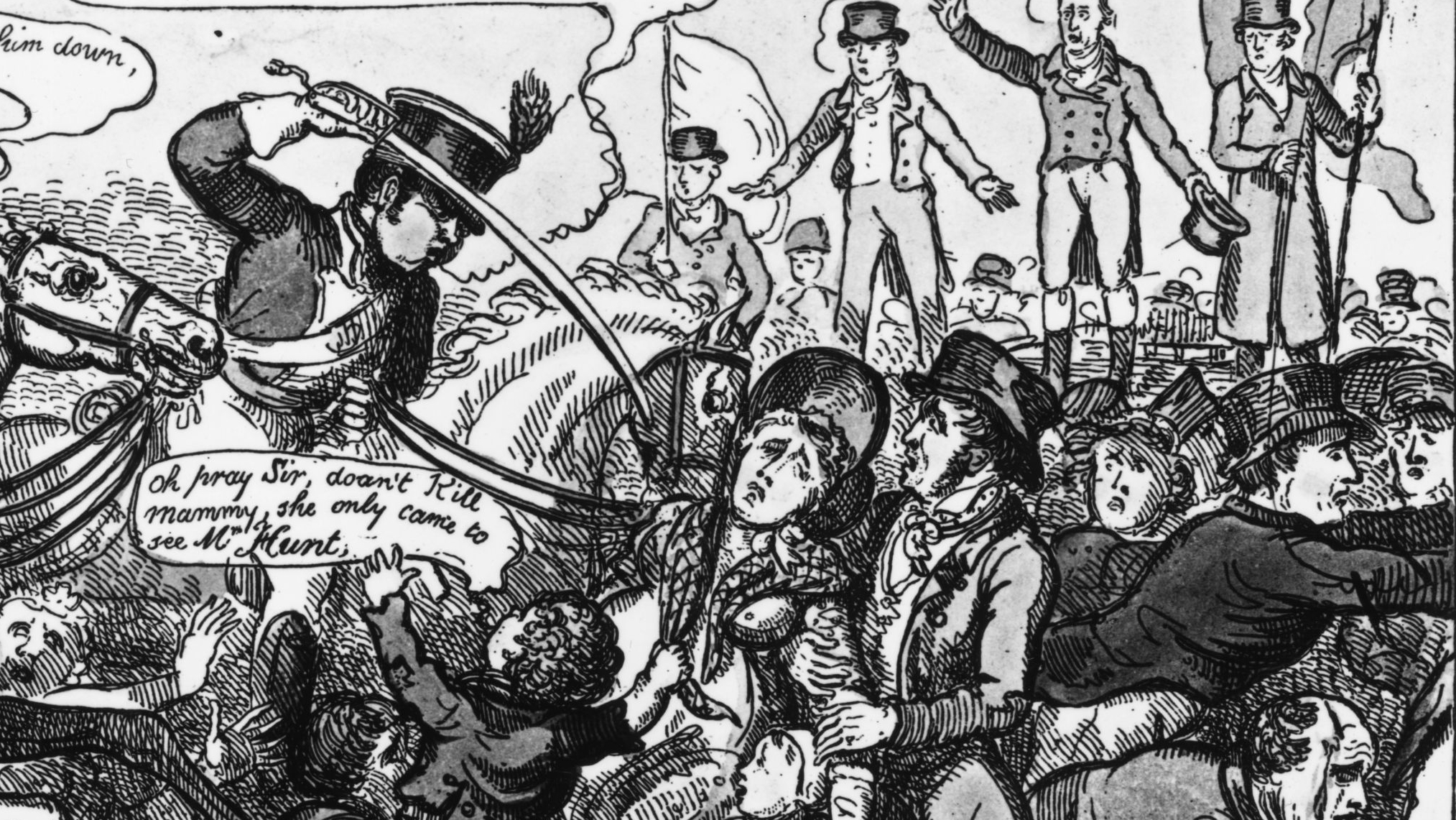

On the afternoon of 16 August, 60,000 men, women and children gathered in Manchester’s St Peter’s Field, now St Peter’s Square, to demand parliamentary reform and to hear radical orator Henry Hunt make a speech calling for increased representation of the working classes, The Times reports.

According to accounts from the time, protesters waved flags bearing populist slogans such as “Liberty and Fraternity” and “Taxation without Representation is Unjust and Tyrannical”.

Frightened by the size of the crowd, the authorities claimed that a violent outbreak could “ignite an English revolution to follow the French” that had ended just 20 years earlier, says The Guardian. City magistrates ordered the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry - a volunteer cavalry regiment who some accused of being drunk - to arrest Hunt and other organisers, but in their chaotic attempt to do so, a number of people were trampled and a two-year-old child killed.

In the ensuing panic, the 15th Hussars, a cavalry regiment in the British Army, were called in to disperse the crowd by William Hulton, chair of the Lancashire and Cheshire Magistrates.

“As the yeomanry became engulfed in the melee, the Hussars charged in after them and the crowd began to flee as best they could, screaming in terror and tripping over each other,” says The Guardian. “Behind them, the troops were striking out with their sabres.”

After 20 minutes of seemingly indiscriminate attacks, the Hussars and Yeomen had dispersed the crowd but left between 11 and 18 people dead, according to different sources. A further 600 were injured.

What was the legacy of the massacre?

The British Library says there was “considerable public sympathy for the plight of the protesters” in the wake of the massacre. However, according to The Guardian, the pervasive view among government loyalists was that the deaths had been “the crowd’s own fault”, and that the protesters were violent, dangerous revolutionaries.

The newspaper - which was founded in Manchester in the wake of the massacre - reports that although Peterloo shocked the nation, it “did not lead directly to parliamentary reform, as the authorities closed ranks against any change”.

Nevertheless, historians generally acknowledge that Peterloo was a milestone event in the struggle to extend the vote, and led to the rise of the Chartist movement that eventually gave rise to trade unionism.

Nick Mansfield, director of Manchester’s People’s History Museum, says Peterloo is a “critical event not only because of the number of people killed and injured, but because ultimately it changed public opinion to influence the extension of the right to vote and give us the democracy we enjoy today”.

“It was critical to our freedoms,” he concludes.