Air pollution is now the 'greatest external threat' to life expectancy

Climate change is worsening air quality globally, and there could be deadly consequences

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

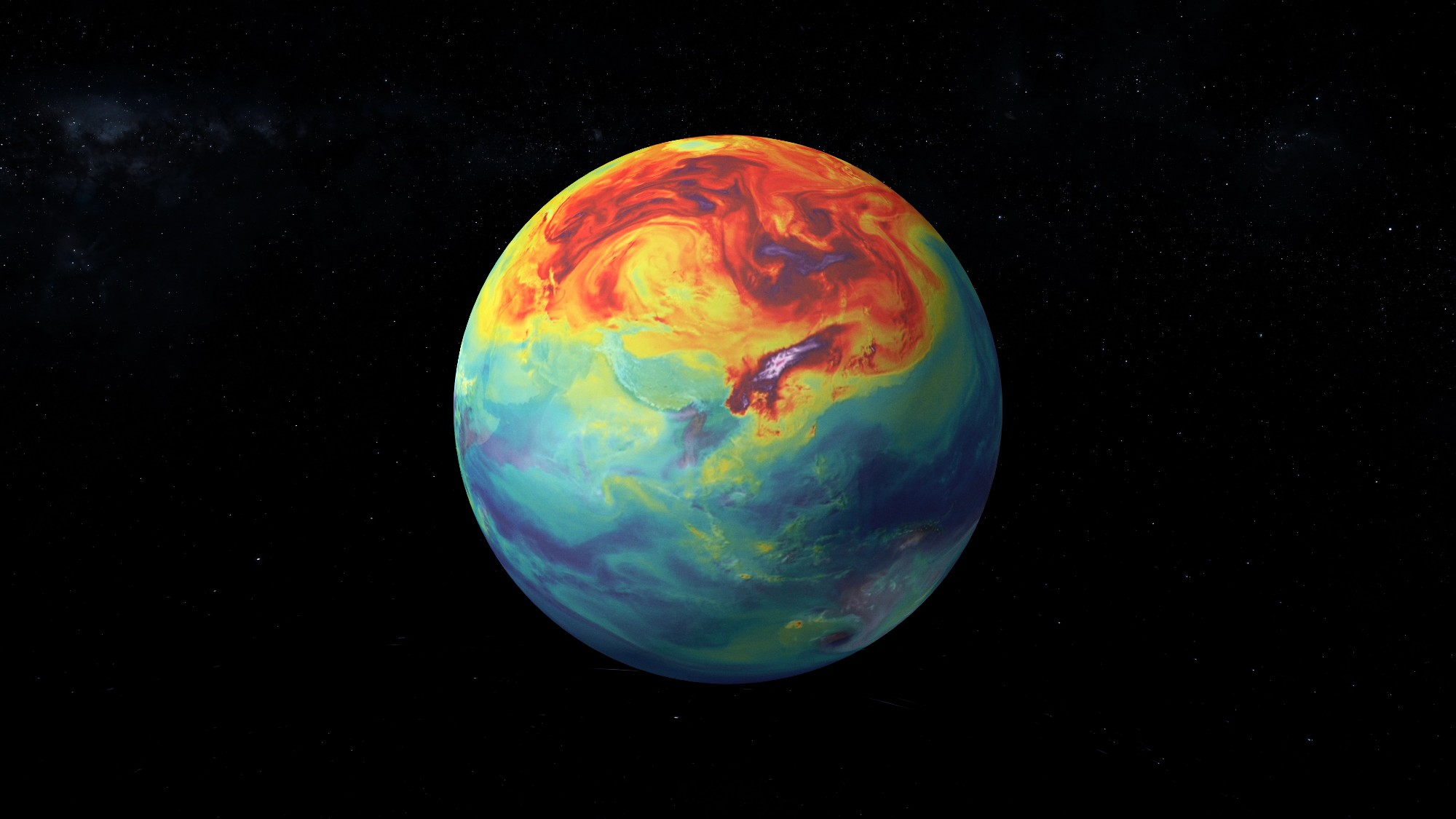

Air pollution has been on the rise due to climate change and has already been proven to have negative health effects, including antibiotic resistance, higher dementia risk, and heart arrhythmia. However, it may be more dangerous than we previously thought.

How dangerous is air pollution?

According to a new study by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC), air pollution is "the greatest external threat to human life expectancy on the planet," and "permanently reducing global PM2.5 air pollution to meet the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline would add 2.3 years onto average human life expectancy." The danger of air pollution is comparable to the danger of smoking, and is more dangerous than alcohol or unsafe water, according to the study.

Certain regions, particularly Asia and Africa, are facing a disproportionate level of risk compared to other places in the world. "There is a profound disconnect with where air pollution is the worst and where we, collectively and globally, are deploying resources to fix the problem," Christa Hasenkopf, director of air quality programs at EPIC, told AFP. Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal, China, Nigeria and Indonesia are the countries most seriously affected by air pollution, accounting for over 75% of global air pollution impact.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

South Asia is the most acutely at risk, as the region contains four of the world's most air-polluted countries in terms of PM2.5 pollutant concentration. "Residents are expected to lose about five years off their lives on average if the current high levels of pollution persist, and more in the most polluted regions," per UChicago News.

Can it be fixed?

"Air pollution improvements are often driven by the demand of the people," Michael Greenstone, an economics professor at the University of Chicago who contributed to the report, told The Wall Street Journal. Improvements also require adequate technology to monitor pollution levels. But not every nation has the proper infrastructure to fight pollution. For example, "air pollution shaves off more years from the average person's life in the DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo) and Cameroon than HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other health threats," and this is largely because an international financing partnership called the Global Fund provides $4 billion annually to the countries to fight on HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, per the report.

"Timely, reliable, open-air quality data in particular can be the backbone of civil society and government clean air efforts," by providing "information that people and governments lack and that allows for more informed policy decisions," Hasenkopf told UChicago News. "Fortunately, we see an immense opportunity to play a role in reversing this by better targeting — and increasing — our funding dollars to collaboratively build the infrastructure that is missing today."

Making change is not impossible, however. China has made great strides in reducing pollution levels in the country. It started its "war on pollution" in 2013 and has since reduced pollution by 42.3 percent. The best way to reduce pollution is to stop the burning of fossil fuels and slow down climate change. Rising temperatures have made regions more susceptible to wildfires which largely add to air pollution.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

What to watch out for at the Winter Olympics

What to watch out for at the Winter OlympicsThe Explainer Family dynasties, Ice agents and unlikely heroes are expected at the tournament

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?

Will Beatrice and Eugenie be dragged into the Epstein scandal?Talking Point The latest slew of embarrassing emails from Fergie to the notorious sex offender have put her daughters in a deeply uncomfortable position

-

How climate change is affecting Christmas

How climate change is affecting ChristmasThe Explainer There may be a slim chance of future white Christmases

-

5 recent breakthroughs in biology

5 recent breakthroughs in biologyIn depth From ancient bacteria, to modern cures, to future research

-

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusion

Why scientists are attempting nuclear fusionThe Explainer Harnessing the reaction that powers the stars could offer a potentially unlimited source of carbon-free energy, and the race is hotting up

-

Canyons under the Antarctic have deep impacts

Canyons under the Antarctic have deep impactsUnder the radar Submarine canyons could be affecting the climate more than previously thought

-

NASA is moving away from tracking climate change

NASA is moving away from tracking climate changeThe Explainer Climate missions could be going dark

-

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?

What would happen to Earth if humans went extinct?The Explainer Human extinction could potentially give rise to new species and climates

-

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkiller

Bacteria can turn plastic waste into a painkillerUnder the radar The process could be a solution to plastic pollution

-

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.

Scientists want to regrow human limbs. Salamanders could lead the way.Under the radar Humans may already have the genetic mechanism necessary