HIV: why the virus could eventually be 'almost harmless'

Scientists have observed an 'incremental change' in HIV which could lead to the virus gradually becoming 'watered down'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

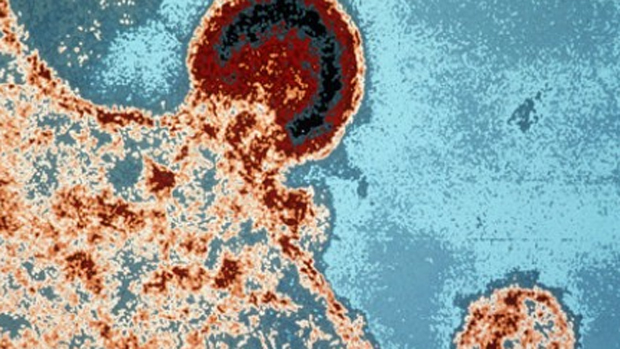

HIV, the virus that causes Aids, may be naturally evolving to become less infectious and less deadly, according to a major new study by Oxford University.

According to the research, HIV appears to be taking longer to transition into Aids as it adapts to the human immune system. Scientists say that HIV may be gradually "watered down," and some virologists believe that the virus may eventually become "almost harmless," the BBC reports.

How does HIV work?

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When HIV enters the body, through sexual contact, blood transfusion or a needle, researchers believe that it attaches itself to a specific type of immune system cell called a dendritic cell, explains Aids.gov. Scientists think that these cells then transmit the virus to the lymph nodes where HIV can then go on to infect other immune cells.

HIV then attacks and kills a crucial type of immune system cell, known as T-helper cells, the Science Museum says. T-helper cells kill off other cells that have been infected with germs, so without them, the human body cannot fight illness.

Someone infected with HIV may not show any symptoms for years, but as their T-helper cell count falls, the risk of infection greatly increases, and eventually the symptoms of Aids can begin to appear.

Why is HIV changing?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

HIV is a "master of disguise," the BBC says. It mutates swiftly in order to evade the immune system. However, when the virus encounters someone with a strong immune system, it finds itself "trapped between a rock and hard place," and faces a choice. "It can get flattened or make a change to survive and if it has to change then it will come with a cost," says Professor Philip Goulder, from the University of Oxford. This may include reducing its own ability to replicate, which in turn makes the virus weaker.

This new "weaker" version of the virus may then spread and a long cycle of "watered down" infection can begin, Goulder says.

The Oxford University team came to its conclusions by comparing versions of HIV found in Botswana and South Africa. The team found that the time between contracting HIV and manifesting Aids was ten per cent longer in Botswana, indicating that it may have seen a "watered down" version of the virus.

Goulder said that the time between contracting HIV and the first emergence of Aids symptoms had moved from 10 to 12.5 years in the last two decades.

What had been seen appears to be "a sort of incremental change, but in the big picture that is a rapid change," he said. "One might imagine as time extends this could stretch further and further and in the future people being asymptomatic for decades."

How significant are the findings?

While the results of the study seem encouraging, Jose Borghans of the University Medical Centre Utrecht in the Netherlands told New Scientist magazine, we should not assume that the same thing is happening in Europe and the US. Different studies in the West have produced different results, indicating variously that HIV is becoming more or less virulent or simply remaining the same.

Professor Andrew Freedman, a reader in infectious diseases at Cardiff University, told the BBC that HIV is still "an awfully long way" from becoming harmless, suggesting that "other events will supersede that, including wider access to treatment and eventually the development of a cure".