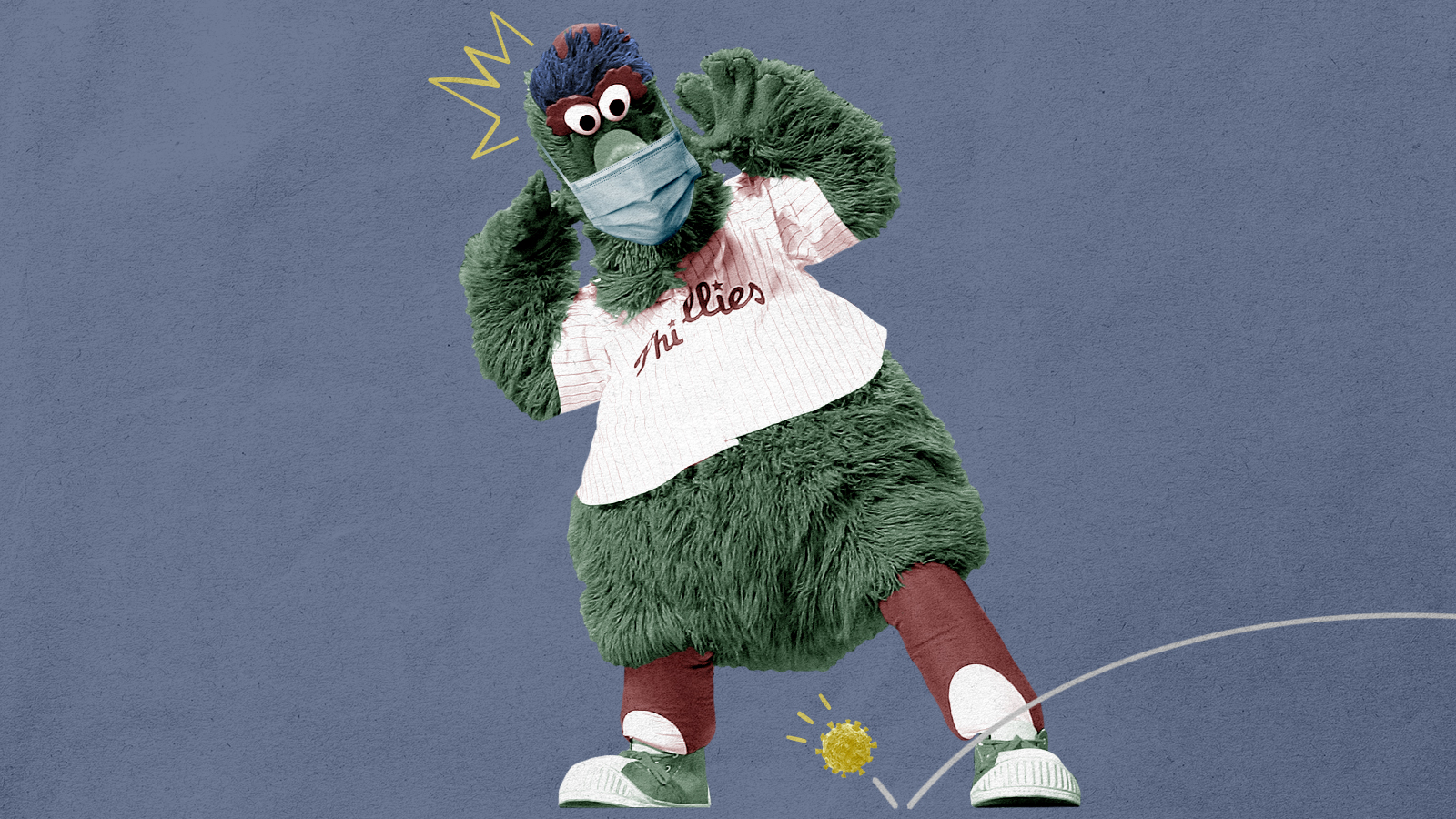

Philly's mask mandate is back, but it's got little to do with COVID

The time for performative disease prevention is over

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I can remember when I assumed the pandemic would end.

It was around a year ago. I had just received my first dose of the Pfizer vaccine, and my wife had just gotten her second shot of Moderna. My daughter was finally back in school after a year spent languishing in remote classes. It felt like we were turning a corner as a country, with the horrific rates of death over the winter of 2021 receding into the past. We weren't out of the woods yet, but we would be soon.

Yet, here we are in mid-April 2022, more than two years into the pandemic, and my own city of Philadelphia has just announced it will be reimposing an indoor mask mandate next week, a little over a month after the city finally dropped it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Instead of having a defined beginning, middle, and end, the pandemic has taken on a different shape, one resembling the cyclical structure of pagan religions more than the linear unfolding of Christian eschatology. The pandemic doesn't end, it evolves, waxing and waning and then waxing again, like cycles of the moon or the tides. Philadelphia enjoyed a month or so of liberation from masks, but now they're coming back. I don't doubt the new mandate will go away at some point, but I doubt very much it will be gone for good.

The mandate is returning now, of course, because the highly contagious Omicron variant that produced a huge surge in cases a few months ago has spawned an even more contagious subvariant labeled BA.2. by the epidemiologists. That sounds ominous — and it is, for those who are unvaccinated and who didn't acquire natural immunity from catching the original version of Omicron over the late fall and winter. For the rest of us — those who are vaccinated, who have received at least one booster shot, and/or who developed antibodies due to a prior brush with Omicron — it will be a risk, but a very small one.

Precisely how small is difficult to say. That's because we can no longer know with anything approaching certainty how widespread the virus is. National numbers of new cases have begun to rise again, after falling for months, and the spike is most pronounced in the Northeast. But for the first time since the pandemic began, home tests are widely available. Results from those who self-test don't get picked up by the government. That means reports of new cases, as well as positivity rates, are now more unreliable than ever. We just don't know how many people are sick — though lagging indicators like rates of COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths, currently at a low ebb, should still be useful and accurate over the coming weeks and months.

Without solid data to document new cases, we're thrown back on anecdote — and by that measure, things are clearly worsening in Philly. A family member who teaches at a university in the city reports that she's never had so many students out sick with COVID. Most are suffering through symptoms that resemble a bad cold or fairly mild flu. That's consistent with what vaccinated and boosted individuals experienced with the original Omicron wave. It's not great, but it's also not an emergency requiring renewed public-health interventions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Or is it? The city of Philadelphia sure seems to think so. The city's health commissioner Cheryl Bettigole acknowledged at a press conference Monday afternoon that the official tally of new cases was still extremely low (just 142, when the seven-day average during the worst of the Omicron wave was nearly 4,000). Yet Bettigole insisted that "this is our chance to get ahead of the pandemic," even though doing so by imposing a new mask mandate when case numbers and hospitalizations are low runs contrary to CDC recommendations.

Pressed on the decision to disregard CDC guidance, Bettigole pointed to … structural racism. "Local conditions" matter, she said. "We've all seen here in Philadelphia, how much our history of redlining, history of disparities has impacted, particularly our Black and brown communities in the city. And so it does make sense to be more careful in Philadelphia, than, you know, perhaps in an affluent suburb."

So, people in an affluent suburb get to decide for themselves whether to don a mask when entering a store or other interior space, but those in Philly will be forced by government fiat to do this because … redlining used to be practiced in the city? I honestly can't parse the statement or construct a coherent line of argument to justify it. (Your freedom was once restricted, so your freedom must be restricted now?) All I know is that starting next week people who live or work in, or who visit, the city will be less free than those who do not. And that the rule will be imposed for reasons that have little to do with a threat to public health.

Residents of Philadelphia, whether they are Black or brown or white, are protected by the vaccines from the worst coronavirus symptoms, and even more so if they receive booster shots in line with current FDA authorizations and recommendations. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the shots turn a positive diagnosis (breakthrough infection) into a few days of unpleasantness rather than a life-threatening event. Doesn't that imply that the number-one priority of health officials should be the broadest possible dissemination of the vaccines, with additional therapeutics made widely available for the very few who develop worse symptoms?

If every person in Philadelphia were vaccinated, would even a single mask be necessary?

That's what's so maddening and demoralizing about this latest turn in the saga of the COVID-19 pandemic: Instead of responding to the persistence of the virus by doing what would permit us to live our lives with as little disruption and as much normalcy as possible, those in positions of power appear to prefer imposing greater restrictions that are also less effective.

That was frustrating when it happened early on in the pandemic, when we were all groping around in the dark, trying to figure out in real time how the virus works and how best to protect against it. But after more than two years and a million deaths and the approval of several effective vaccines that for nearly everyone who takes them have turned COVID-19 into something about as deadly and debilitating as the flu, strep throat, or bronchitis, it's worse than frustrating. It's something closer to infuriating.

I'm not a troublemaker, so I'll obey the mask mandate when I'm in the city, starting next week. But I won't be doing it to keep myself safe. I'll be doing it in order to conform to rules imposed by public officials for little reason.

When it comes to my own health, I'll be taking that into my own hands when I get my second vaccine booster at the beginning of May, six months after the last one. The prospect of living with endemic COVID-19 would seem much less intolerable if that's all any of us were expected to do.

Maybe someday it will be. All I know if that for now, in Philadelphia and most likely other cities very soon, we aren't there yet.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’