A brief history of the centuries-old relationship between Ukraine and Russia

The two countries have a history going back to the 9th century

Justin Klawans, The Week US

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The history of what we now think of as Russia started in Kyiv more than 1,000 years ago when Viking warrior-merchants came down from the north and founded Kyivan Rus, the first East Slavic state, in the 9th century. But that common origin doesn't mean Russia and Ukraine are one big happy family. Russian President Vladimir Putin has long claimed that Ukraine is part of the Russian world — a claim soundly rejected by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Modern Ukraine has been independent since 1991 after centuries of in-fighting and rule by others, including the Mongols, Poland, Lithuania, the Austrio-Hungarian Empire, Nazi Germany and more. Now, the history of these countries has culminated in a bloody war entering its third year.

How is Ukraine's history intertwined with Russia's?

Kyivan Rus reached its zenith with the rule of Prince Volodymyr the Great and his son Yaroslav the Wise in the 10th and 11th centuries. Volodymyr embraced Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 988, establishing the religious tradition still dominant in Ukraine and Russia.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Kyivan Rus fell to Mongol invaders in the 13th century, and Poland took control of much of what is now western and northern Ukraine in the 14th century. The center of Rus power migrated to the small trading post called Moscow.

Ukrainian Cossack leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky made a stab at creating an independent Ukraine in the mid-17th century. But in a bid to push Poland out of Ukraine, he signed the Pereyaslav Agreement with the Russian czar Alexis in 1654, pledging to place an autonomous Ukraine under Russian rule in exchange for Russian military assistance. Even after thousands of years of tensions, Russia and Ukraine have "never entirely untangled that history and gone their separate ways," said NPR.

Why does Russia lay claim to Ukraine?

Along with their common origin in 9th century Kyiv, Russia has controlled much or all of Ukraine for the past 350 years. Russia values the fertile plains and rich, dark soil that has made Ukraine the "breadbasket of Europe." Putin also "wants to reestablish directly or indirectly, by annexation or by puppet regimes, a Russian Empire," said Hein Goemans, a professor of political science at the University of Rochester.

By the late 1700s, Imperial Russia had absorbed most of western Ukraine from Poland and taken the Crimean Peninsula from the Tatars. The czars in St. Petersburg controlled what they called "Little Russia" until the Russian Empire crumbled in 1917 and Ukraine declared independence. That first independent state did not last long. Poland invaded from the West, and Red (Bolshevik) and White (anti-Bolshevik) Russian forces fought Ukrainian troops and each other. When the Red Army emerged victorious in 1921, the eastern two-thirds of the battered and impoverished Ukraine became the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Except for a brief and terrible period of Nazi German occupation, the Soviet Union controlled Ukraine, using various degrees of repression and brutality, until the USSR collapsed in 1991. But even after Russia agreed to respect Ukraine's post-Soviet borders in 1994's Budapest Memorandum, it never fully gave up designs on its smaller neighbor. Putin certainly hasn't.

Putin annexed Crimea — which Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had abruptly, somewhat mysteriously given Ukraine in 1954, ostensibly to mark the 300th anniversary of the Pereyaslav Agreement — in 2014, then launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

What's Putin's argument?

Putin initially justified his invasion as a limited operation to "de-Nazify" Ukraine and protect the large number of ethnic Russians and Russophones in the eastern Donbas region. But in a Nov. 28, 2023, speech sponsored by the Russian Orthodox Church, he claimed that the "Russian nation" comprises a "triune people" of Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians, echoing historically skewed assertions he made in his pre-invasion "Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians" essay in July 2021.

The first Russian history textbook was written and published in Kyiv in the 1670s, and historically, Russians and Ukrainians do "have a lot in common," including "the structure of society, the level of education, the level of urbanization and other things," thanks to hundreds of years of Russian rule, historian Serhii Plokhy said to Harvard's Ukrainian Research Institute in 2017. But even Soviet leader Joseph Stalin — who killed millions of Ukrainians in his engineered 1923-33 famine, the Holodomor — "never questioned per se the right of the Ukrainian nation to exist. When Putin pushes the idea that Russians and Ukrainians are the same people, he doesn't mean that Russians are Ukrainians. The underlying argument is that Ukrainians are really Russians."

While international observers may disagree, Putin "fervently believes that Russians and Ukrainians are the same people," and has spoken of "his desire to recover Russia's 'historical lands' without specifying what they are," said the Council on Foreign Relations. It is clear, though, that Ukraine is a major part of this plan.

How has Russia exerted control over Ukraine?

Russian authorities would typically crack down on Ukrainian culture, curtailing or even banning the use of the Ukrainian language, forcing the Uniate Catholics to convert to the Russian Orthodox Church, purging local officials, killing or exiling intellectuals, poets and dissidents, and using other levels to pacify or Russify the population.

The Soviet Union confiscated farmland and collectivized agriculture in Ukraine — it was peasant opposition to collectivization that prompted Stalin's brutal starvation campaign — and transferred Russians into eastern Ukraine and, after deporting hundreds of thousands of Tatars to Siberia, the Crimean Peninsula. Soviet leaders also exercised control over Ukraine by handpicking its leaders. After the fall of the USSR, Russia maintained leverage through the sale of subsidized oil and natural gas supplies and backing pro-Russian Ukrainian politicians.

When did Ukraine become its own country?

Until the 20th century, "the goal of Ukrainian activists was autonomy, not independence," Plokhy said. Then, "in the 20th century, we had five attempts to declare an independent Ukrainian state. The fifth succeeded in 1991." In a referendum held in December 1991, more than 92% of Ukrainians voted for independence, including a slight majority in Russo-centric Crimea. To gauge how Ukraine felt about Russia at the time, Ukraine's second democratically elected president, Leonid Kuchma, published a book called "Ukraine Is Not Russia." That's probably unique to Ukraine, Plokhy said. "You can't imagine President [Emmanuel] Macron writing 'France Is Not Germany' or anything like that."

Russian-backed candidate Viktor Yanukovych won the presidency in 2010 and decided in 2013 to scrap plans to sign an association agreement with the European Union that was strongly opposed by Moscow. That sudden halting of further integration with Europe sparked street protests and the eventual occupation of Kyiv's Maidan (Independence) Square. After security forces killed dozens of protesters in January and February 2014, Yanukovych fled to Russia instead of risking a looming impeachment vote. The next month, Russia annexed Crimea, and the month after that, heavily armed pro-Russian forces with Russian weapons and no insignia on their uniforms started attacking government buildings in eastern Ukraine. Putin launched his full-scale invasion eight years later.

In some important ways, Putin's violent efforts to subsume Ukraine into "Big Russia" have backfired, cementing Ukraine's sense of independent national identity aligned with Europe.

Russia and Ukraine are bound together by history and geography — but Putin sees danger in that symbiosis, convinced that "the emergence of a genuinely independent, democratic and Western-leaning Ukraine would eventually pose an existential threat to Russia itself," Peter Dickinson said at the Atlantic Council's UkraineAlert Service.

Ukraine persists even as the third year of war approaches. Ukrainian "national pride is understandably booming," said Kristina Hook at UkraineAlert. But "for most Ukrainians, the main factor fueling their determination to fight on is the sense that Russia's genocidal objectives leave them with no choice but to resist. Either Ukrainians defend themselves, or Ukraine itself will cease to exist."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?In Depth Historian Serhii Plokhy explains why the Kremlin’s nuclear proliferation has begun a dangerous new era of mutually assured destruction

-

How Putin misunderstood his past victories

How Putin misunderstood his past victoriesIn Depth Though Vladimir Putin has led Russia to a number of grisly military triumphs, they may have misled him when planning the invasion of Ukraine

-

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear Armageddon

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear ArmageddonIn Depth After the US and Soviet Union became capable of Mutually Assured Destruction, safeguards were put in place to prevent World War Three

-

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animals

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animalsUnder the Radar A human skeleton definitively shows damage from a lion's bite

-

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaboration

Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaborationUnder the Radar The archives were available to researchers but only recently became publicly accessible

-

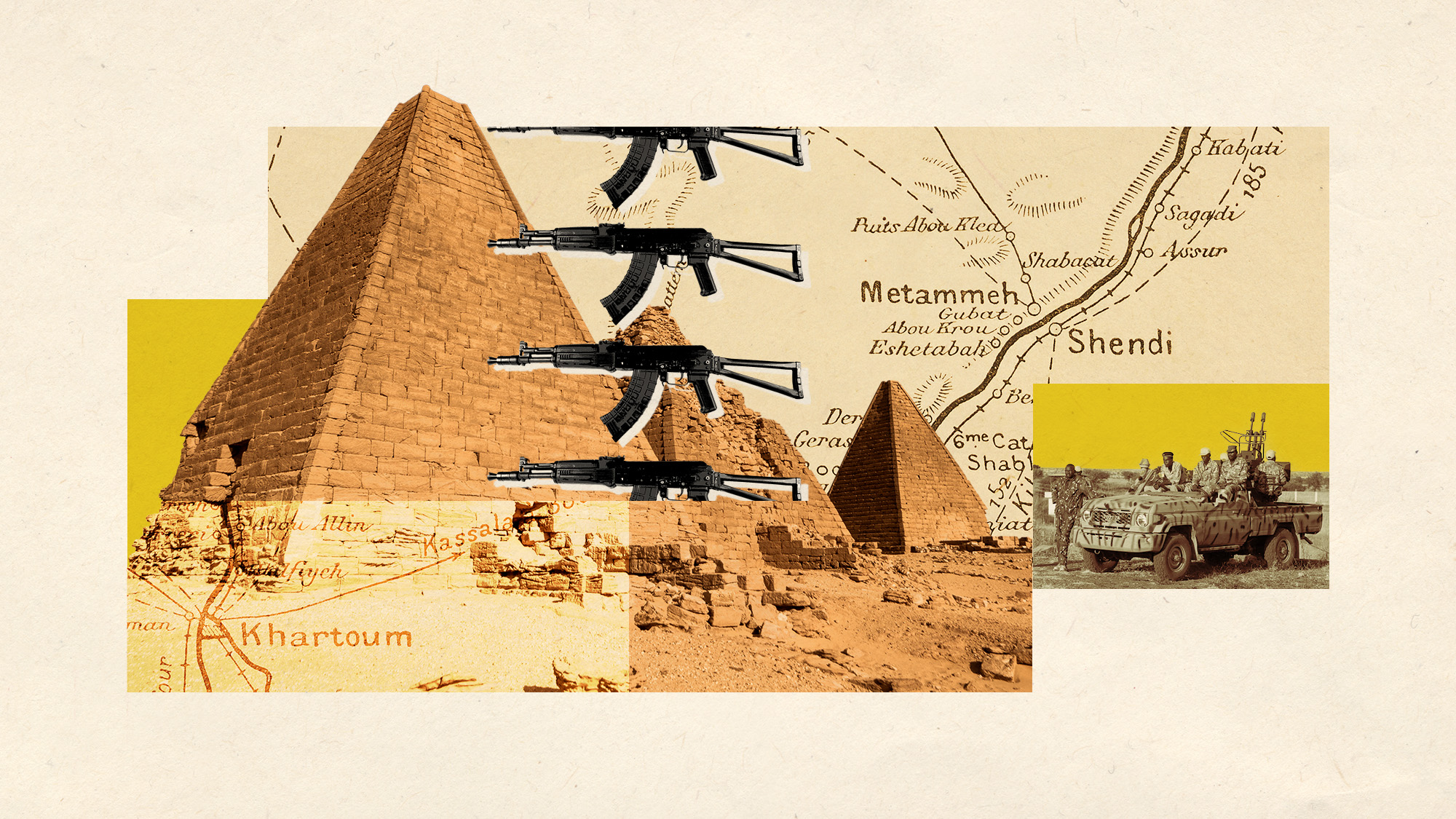

Sudan's forgotten pyramids

Sudan's forgotten pyramidsUnder the Radar Brutal civil war and widespread looting threatens African nation's ancient heritage

-

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raid

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raidSpeed Read She was the first woman to oversee an American military action during a time of war