Why infant mortality is rising

The infant mortality rate recently rose for the first time in two decades

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

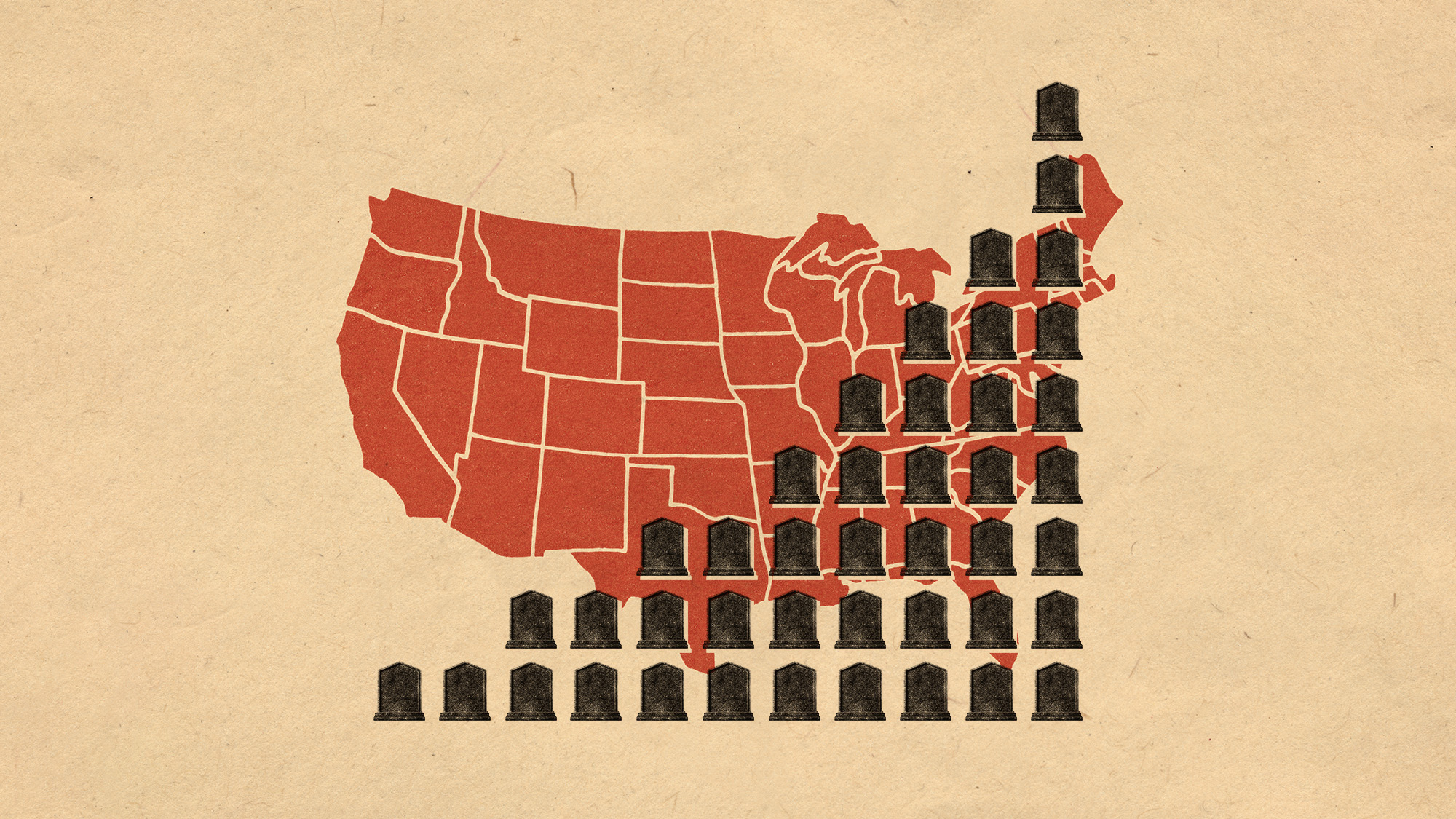

The infant mortality rate in the United States recently rose for the first time in two decades, according to a provisional report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Vital Statistics. U.S. infant mortality rose 3% from 2021 to 2022, which has raised concern among experts given that it had been on the decline in previous years.

It’s not just babies, though, as their mothers are also facing similar health risks. Maternal mortality has been rising steadily, indicating a reduction in society’s overall health. The U.S.' rates are "higher than those in other industrialized countries," per The New York Times, which is the "somber manifestation of the state of maternal and child health in the United States."

Why is infant mortality rising?

While the report doesn’t pinpoint a specific reason for the decline, experts blame the lack of emphasis on maternal and infant healthcare. As a developed country, the United States "should be doing some of the basics better," Elizabeth Cherot, the chief executive of the infant and maternal health nonprofit March of Dimes, told The Wall Street Journal. "Too many babies are dying in the United States." Many regions of the country have become maternal care deserts which also inhibits the access to infant care.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Worsening maternal healthcare was exacerbated by the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, causing some states to place strict restrictions on abortion access. "Any pregnancy that is intended and planned tends to be a healthier outcome and healthy infant outcome," Tracey Wilkinson, an associate professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, told ABC News. "So, when you remove the ability for people to decide if and when to have families and continue pregnancies, ultimately, you are having more pregnancies continue that don't have all those factors in place." In addition, most of the infant deaths in the report were born in 2022 after being conceived in 2021, when the pandemic was in full swing. This also likely contributed to the higher mortality rate, given the risks from the pandemic to infant health.

While infant mortality rates increased across almost all ethnic groups, Black and Indigenous mothers were disproportionately impacted, and face "up to double the risk of dying, compared with white and Hispanic babies," per the Times. "Disparities in health care and outcomes exist in everything," Wilkinson said. "When you have restrictions to health care access, that always impacts minoritized communities more and what this data is showing is that now it's also impacting non-minoritized communities like white women."

What can be done to reduce it?

The U.S. can improve infant mortality rates by "following the examples of other developed countries with comparatively low infant mortality rates, where public health authorities devote more attention to mothers and babies," the Journal wrote. "The U.S. is falling behind on a basic indicator of how well societies treat people," Arjumand Siddiqi, a public health and epidemiology professor at the University of Toronto, told the outlet. "In a country as well-resourced as the U.S., with as much medical technology and so on, we shouldn’t have babies dying in the first year of life."

Two of the leading causes of infant deaths were maternal complications and bacterial sepsis, which can occur when babies "contract infections from their mothers during birth, or when a bacteria infects an infant at home who isn’t immediately treated for it," the Journal added. These can both be avoided with access to proper maternal care. "You're gonna have people delivering at hospitals that don't have the expertise to take care of moms that get sick during pregnancy and delivery and infants that get sick very soon after delivery, which is what I think of as bacterial sepsis of newborns," Wilkinson explained. Experts have continually concluded that infant and maternal health are closely linked, and improving access to care is necessary to reduce both.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this century

Deaths of children under 5 have gone up for the first time this centuryUnder the radar Poor funding is the culprit

-

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancy

Stopping GLP-1s raises complicated questions for pregnancyThe Explainer Stopping the medication could be risky during pregnancy, but there is more to the story to be uncovered

-

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violence

RFK Jr. sets his sights on linking antidepressants to mass violenceThe Explainer The health secretary’s crusade to Make America Healthy Again has vital mental health medications on the agenda

-

Nursing is no longer considered a professional degree by the Department of Education

Nursing is no longer considered a professional degree by the Department of EducationThe Explainer An already strained industry is hit with another blow

-

Nitazene is quietly increasing opioid deaths

Nitazene is quietly increasing opioid deathsThe explainer The drug is usually consumed accidentally

-

More adults are dying before the age of 65

More adults are dying before the age of 65Under the radar The phenomenon is more pronounced in Black and low-income populations

-

The plant-based portfolio diet invests in your heart’s health

The plant-based portfolio diet invests in your heart’s healthThe Explainer Its guidelines are flexible and vegan-friendly