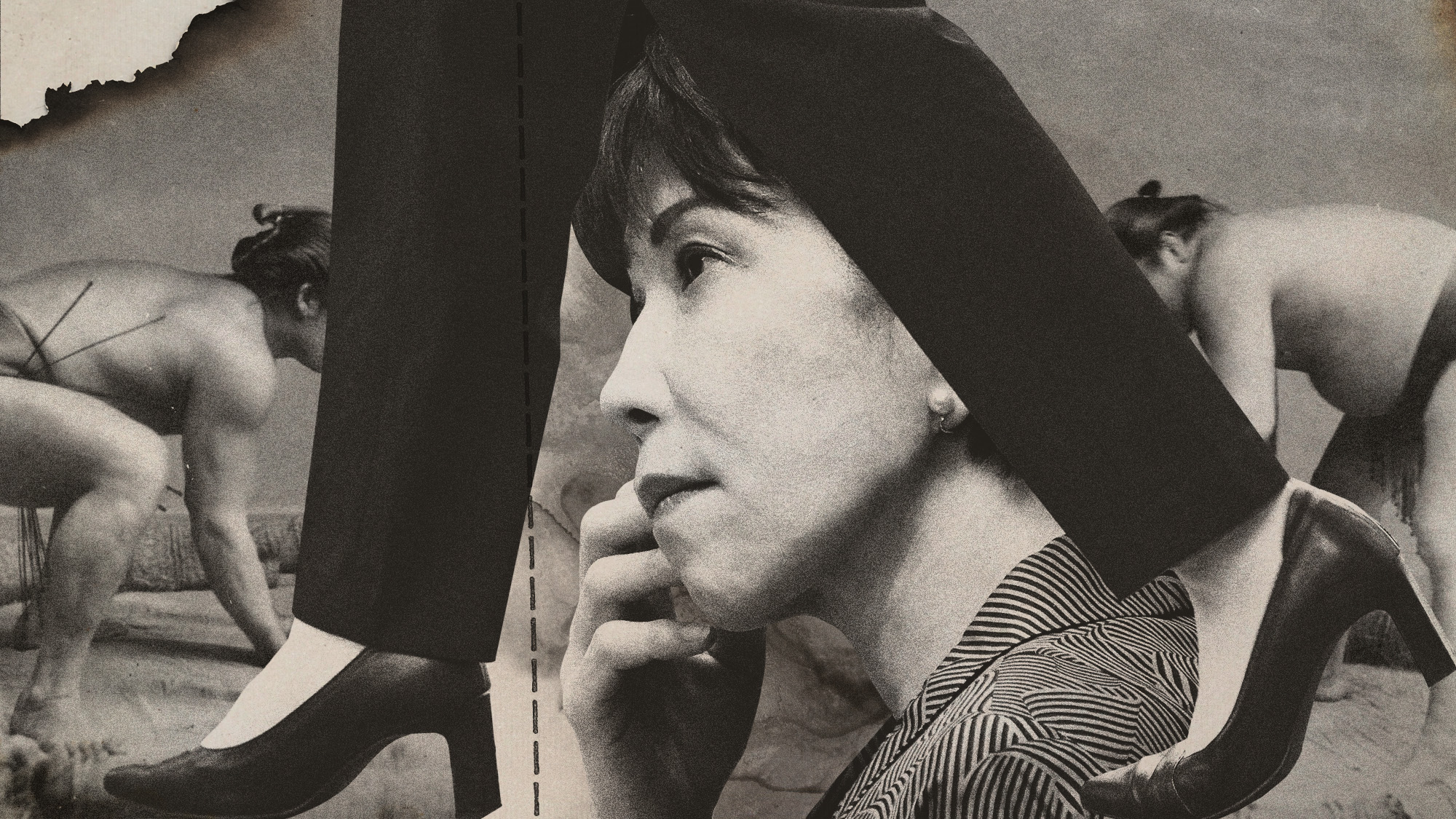

Will Japan’s first female prime minister defy sumo’s ban on women?

Sanae Takaichi must decide whether to break with centuries of tradition and step into the ring to present a trophy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The sumo ring has always been a “sacred” arena where “only men may tread, bound by centuries of ritual and pride”, said The Japan Times. But now that Japan has elected its first female prime minister, the question arises: “If she can stand at the centre of power, why not in the centre of the ring?”

It won’t be long before this thorny question faces a “real-world test”. On 23 November, Sanae Takaichi will have to decide whether to break with tradition and step into the sumo ring (dohyo), to present the trophy to the Grand Sumo champion in Fukuoka.

‘Off-limits’ for women

Sumo rings remain “off-limits” to women and girls. Known as nyonin kinsei (female exclusion), the practice is rooted in Shinto beliefs around impurity – “particularly the idea that blood from death, childbirth or menstruation can defile what is sacred”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The ban has sparked controversy for decades. In 1990, Mayumi Moriyama, Japan’s first female cabinet minister, asked the Japan Sumo Association (JSA) if she could present a trophy on behalf of the prime minister. Her request was rejected. Ten years later, Osaka’s then governor, Fuse Ohta, “was forced to present a prize to the champion of the annual Osaka tournament on a walkway next to the dohyo”, said The Guardian.

More recently, in 2018, the local mayor suffered a stroke during a speech in a sumo arena in Maizuru, near Kyoto. A female nurse was among the spectators who “rushed on to the ring to administer first aid”. The referee repeatedly called for her to leave the dohyo, and officials “sprinkled ‘purifying salt’ on the wrestling surface”, although they later denied this was because of her presence. Still, the incident sparked an “outcry” and the JSA chair was “forced to apologise”. But days later, Tomoko Nakagawa (the then mayor of Takarazuka), was made to deliver a speech to the side of a ring, telling spectators she was “mortified” by her treatment as a woman.

Barring women from the sumo ring is “part of a broader societal affliction”, said The Economist. Japan ranks 118th out of 148 countries in the World Economic Forum’s global gender gap index. “That is better than Saudi Arabia but worse than Bahrain.”

Away from sport, until the 2000s women were “prohibited from tunnel construction sites owing to the belief that their presence would make the female mountain god jealous and bring misfortune”, and are still banned from climbing some sacred mountains, including Mount Ōmine in Yoshino-Kumano National Park.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

‘Quiet resistance’

Despite its deeply conservative roots, sumo is facing “quiet resistance”, said The Associated Press. While professional sumo remains out of bounds for women, a “small but growing group of more than 600 wrestlers is making strides at the amateur level in Japan”. Like men, they wear the traditional loincloth – but instead of competing bare-chested, they wear it over shorts or leotards.

As the Grand Sumo tournament draws to its conclusion, some hope the appointment of Takaichi as PM could “herald change”, said The Economist. Will she finally “break the taboo?” If Japan’s prime minister were to step into the dohyo, it would be a “symbolic victory for women’s rights campaigners”, said The Guardian.

But Takaichi, a social conservative who opposes women having the right to keep their maiden name after marriage, looks unlikely to rock the boat. “The prime minister wishes to respect sumo tradition and culture”, said Minoru Kihara, the chief cabinet secretary. “The government has not yet made a decision on the matter.”

The JSA said it had formed a panel to look into the issues back in 2018, but it has yet to reach its conclusion. “Sumo is still hiding behind vague words like ‘tradition’ and ‘custom’”, Nakagawa told The Japan Times. “That era is over. If we let this moment slip by, nothing will ever change.”

Irenie Forshaw is the features editor at The Week, covering arts, culture and travel. She began her career in journalism at Leeds University, where she wrote for the student newspaper, The Gryphon, before working at The Guardian and The New Statesman Group. Irenie then became a senior writer at Elite Traveler, where she oversaw The Experts column.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What India’s World Cup win means for women’s cricket

What India’s World Cup win means for women’s cricketIn The Spotlight The landmark victory could change women’s cricket ‘as we know it’

-

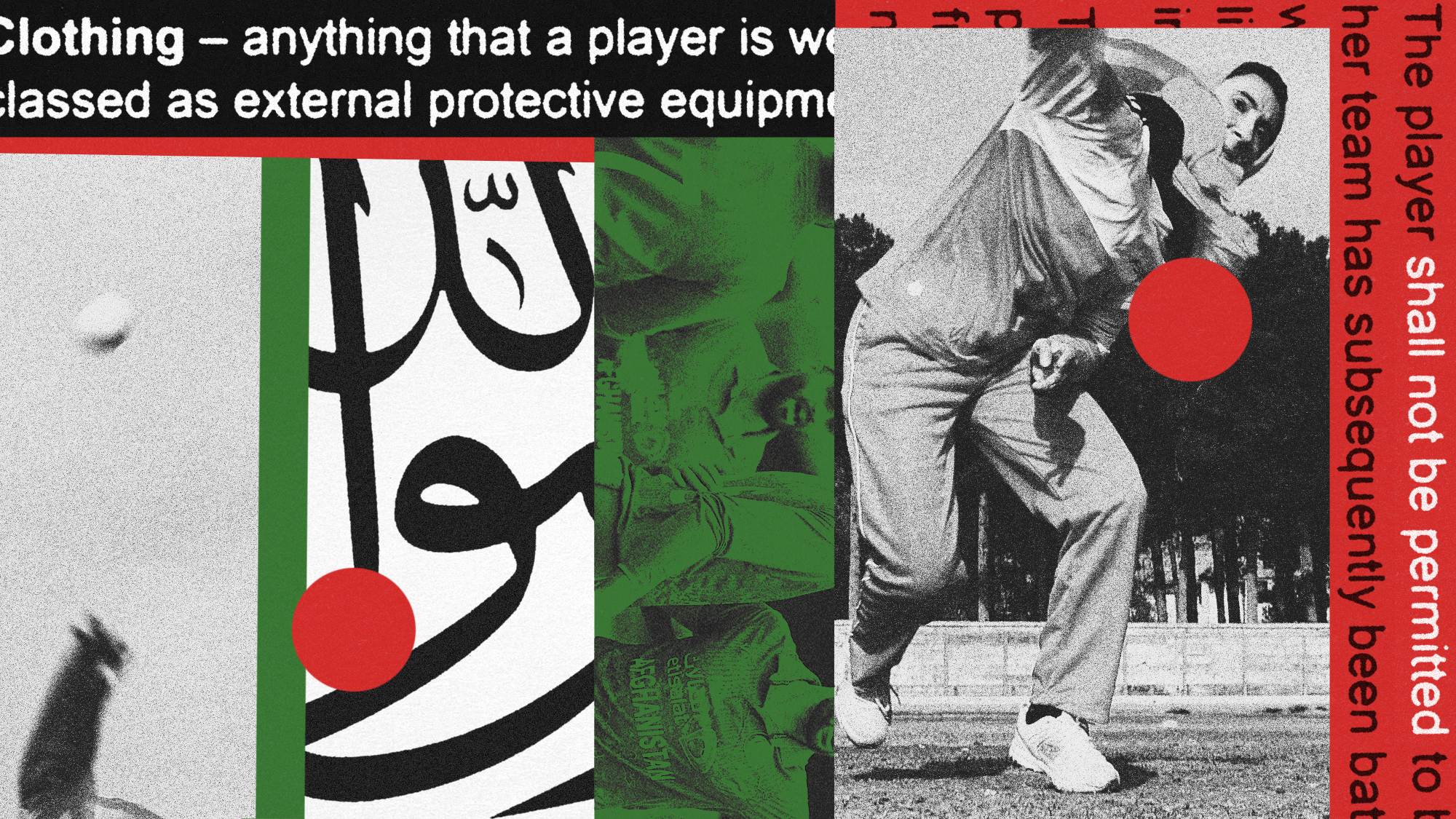

How should the cricketing world handle Afghanistan?

How should the cricketing world handle Afghanistan?Talking Point England under pressure to boycott upcoming men's match against the nation, which remains an ICC member despite Taliban ban on women's team

-

Women are getting their own baseball league again

Women are getting their own baseball league againIn the Spotlight The league is on track to debut in 2026

-

Should American pro sports ditch their player drafts?

Should American pro sports ditch their player drafts?Talking Points Why the NWSL is embracing free agency for new players

-

Biles takes all-around gold at Olympics

Biles takes all-around gold at OlympicsSpeed Read Simone Biles won the women's Olympic all-around gymnastics competition in the Paris Games

-

Biles wins 9th national title ahead of Olympics

Biles wins 9th national title ahead of OlympicsSpeed Read She swept every individual event at the U.S. Gymnastics Championship

-

DOJ settles with Nassar victims for $138M

DOJ settles with Nassar victims for $138MSpeed Read The settlement includes 139 sexual abuse victims of the former USA Gymnastics doctor

-

Caitlin Clark the No. 1 pick in bullish WNBA Draft

Caitlin Clark the No. 1 pick in bullish WNBA DraftSpeed Read As expected, she went to the Indiana Fever