Normalising relations with the Taliban in Afghanistan

The regime is coming in from the diplomatic cold, as countries lose hope of armed opposition and seek cooperation on counterterrorism, counter-narcotics and deportation of immigrants

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the Taliban swept across Afghanistan and retook power in 2021, most countries severed diplomatic ties, but now India is leading a change of heart around the world.

Despite claims that its second iteration – what some termed “Taliban 2.0” – would be more moderate, the group reintroduced its draconian restrictions on women and girls to international condemnation. The UN Security Council imposed strict sanctions and froze large assets, saying the regime was enacting a “gender apartheid”.

This year, Russia became the first country to formally recognise the Taliban government. Over the past few months, said the Financial Times, the regime “has begun to emerge from diplomatic isolation”, as countries see a potential ally in trade, counterterrorism and the deportation of migrants.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What has happened recently?

India used to see the Taliban as a threat, given its extremist ideology and its closeness with arch-enemy Pakistan. But New Delhi has been trying to improve engagement. In October, it hosted foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi: the first diplomatic trip abroad by a senior Taliban official since the group’s return to power. Although he required a visa waiver due to UN sanctions, the “rapturous reception” he received is “one of the most striking signs of how the world is warming up to the Taliban”, said the FT.

After the visit, New Delhi announced that it would be “upgrading its technical mission” in Kabul to “a full-fledged embassy”, said Al Jazeera. “Closer cooperation between us contributes to your national development, as well as regional stability and resilience,” said Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar. Speaking to reporters, Muttaqi said: “We want good relations; we keep our doors open for talks – for all!”

Why is India normalising relations?

For India, the Taliban “represents a ‘lesser evil’” compared with terrorist groups such as al-Qaida and Isis-K, said Chietigj Bajpaee of Chatham House’s South Asia, Asia-Pacific Programme. India wants to stop Afghanistan from “re-emerging as a hub for militancy and terrorism”.

Unlike during the 1990s, when India, Iran and Russia backed forces that opposed the Taliban, now there is almost no armed opposition in Afghanistan. “The Indians are being very pragmatic, having realised that the Taliban is the only game in Kabul and that they are not going anywhere”, a senior Pakistani diplomat told the FT. They see it as: “the enemy of my enemy could be my friend’ and the Taliban is clearly taking advantage of that”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What about the rest of the world?

When Russia formally recognised the Taliban government in July, its foreign ministry said it saw potential for “commercial and economic” cooperation, said the BBC. Russia also wants to cooperate with Afghanistan on counterterrorism, after the deadly Islamic State attack on a concert hall in Moscow in 2024, and to increase trade.

China was the first country to accredit an ambassador from the Taliban, and has pursued what analysts describe as “durable de facto recognition”, eyeing Afghanistan’s reserves of critical minerals and resources.

In the West, the US has praised the Taliban for its crackdown on Isis-K. Sebastian Gorka, a counterterrorism adviser to Donald Trump, revealed in August that Washington and the Taliban were “working together” to fight Islamist militancy. European countries have lauded the Taliban’s destruction of fields of opium poppies, a key ingredient in heroin production, and are also increasingly keen to engage with Afghanistan on the repatriation of migrants. Germany, Switzerland and Austria have all recently sent delegations or welcomed Taliban officials; Germany says it wants to work with the group directly to resume deportations of convicted Afghans.

What’s in it for the Taliban?

Afghanistan is battling endemic poverty and the fallout from natural disasters like the earthquake in August, exacerbated by devastating US aid cuts. Iran and Pakistan have also forcibly returned more than four million Afghans in two years, said the International Organization for Migration, causing chaos at the border and further strain on resources. The Taliban hopes its increased international engagement will “translate into much-needed economic aid and investments”, said the FT. But there is “little sign of this taking place yet”. The oppression of women and girls is the “primary issue facing Afghanistan’s economic future”, said UN Assistant Secretary-General Kanni Wignaraja.

“The Taliban still presides over a pariah state, shunned by most of the world,” said Modern Diplomacy. Its “partial diplomatic thaw” has brought no “real economic relief”; it “remains locked in a dangerous cross-border dispute with Pakistan and trapped by financial isolation”.

Islamabad historically supported the Taliban and saw Afghanistan as a “source of ‘strategic depth’ in its rivalry with India”, said Bajpaee. Now, it is accusing the Afghan Taliban of hosting and sponsoring the militant Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP or Pakistani Taliban), which aims to “overthrow the Pakistani state” and has “stepped up its attacks inside Pakistan”. Pakistan increasingly sees its neighbour as a “liability”.

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff war

EU and India clinch trade pact amid US tariff warSpeed Read The agreement will slash tariffs on most goods over the next decade

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Will the mystery of MH370 be solved?

Will the mystery of MH370 be solved?Today’s Big Question New search with underwater drones could finally locate wreckage of doomed airliner

-

Pakistan: Trump’s ‘favourite field marshal’ takes charge

Pakistan: Trump’s ‘favourite field marshal’ takes chargeIn the Spotlight Asim Munir’s control over all three branches of Pakistan’s military gives him ‘sweeping powers’ – and almost unlimited freedom to use them

-

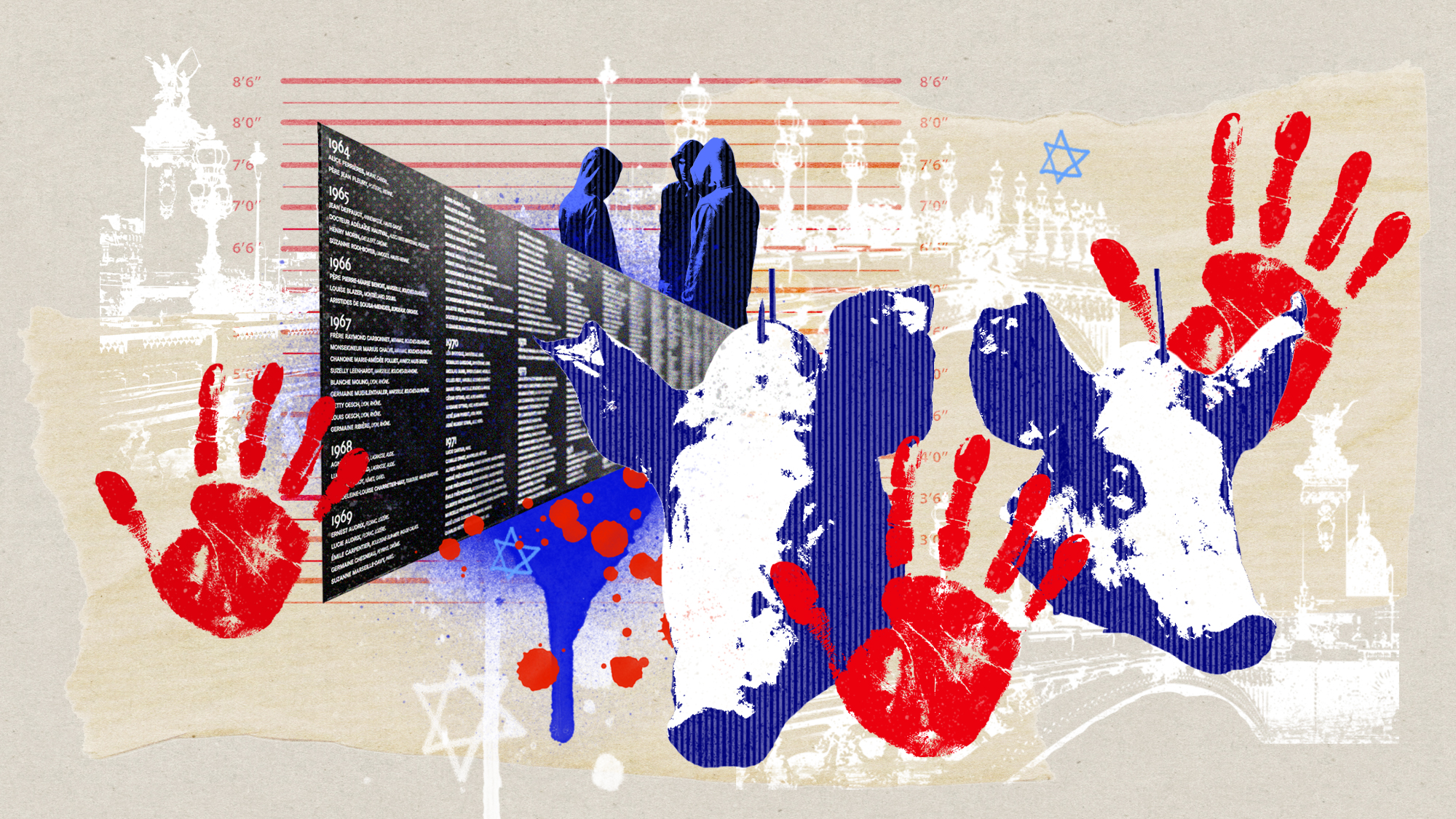

France’s ‘red hands’ trial highlights alleged Russian disruption operations

France’s ‘red hands’ trial highlights alleged Russian disruption operationsUNDER THE RADAR Attacks on religious and cultural institutions around France have authorities worried about Moscow’s effort to sow chaos in one of Europe’s political centers

-

Sanae Takaichi: Japan’s Iron Lady set to be the country’s first woman prime minister

Sanae Takaichi: Japan’s Iron Lady set to be the country’s first woman prime ministerIn the Spotlight Takaichi is a member of Japan’s conservative, nationalist Liberal Democratic Party

-

Will Starmer’s India visit herald blossoming new relations?

Will Starmer’s India visit herald blossoming new relations?Today's Big Question Despite a few ‘awkward undertones’, the prime minister’s trip shows signs of solidifying trade relations

-

The Taliban wages war on high-speed internet

The Taliban wages war on high-speed internetTHE EXPLAINER A new push to cut nationwide access to the digital world is taking Afghanistan back to the isolationist extremes of decades past